Once upon a time hard disks were expensive. A device that could hold a terrabyte would cost hundreds of thousands in the late 1990’s! I remember Windows NT 3.51 taking 3 days to format 890GB!!!

Once upon a time hard disks were expensive. A device that could hold a terrabyte would cost hundreds of thousands in the late 1990’s! I remember Windows NT 3.51 taking 3 days to format 890GB!!!

Even when I got my first 20MB hard disk, it along with the controller cost several hundred dollars. I had upgraded to a 286 from a Commodore 64, and even a 720kb floppy felt massive! I figured it’d take a long while to fill 20MB so I was set. Well needless to say I was so wrong! Not to mention there was no way I could afford a 30MB disk, I wasn’t looking for a questionable used 10MB disk, and a 40MB disk was just out of the question!

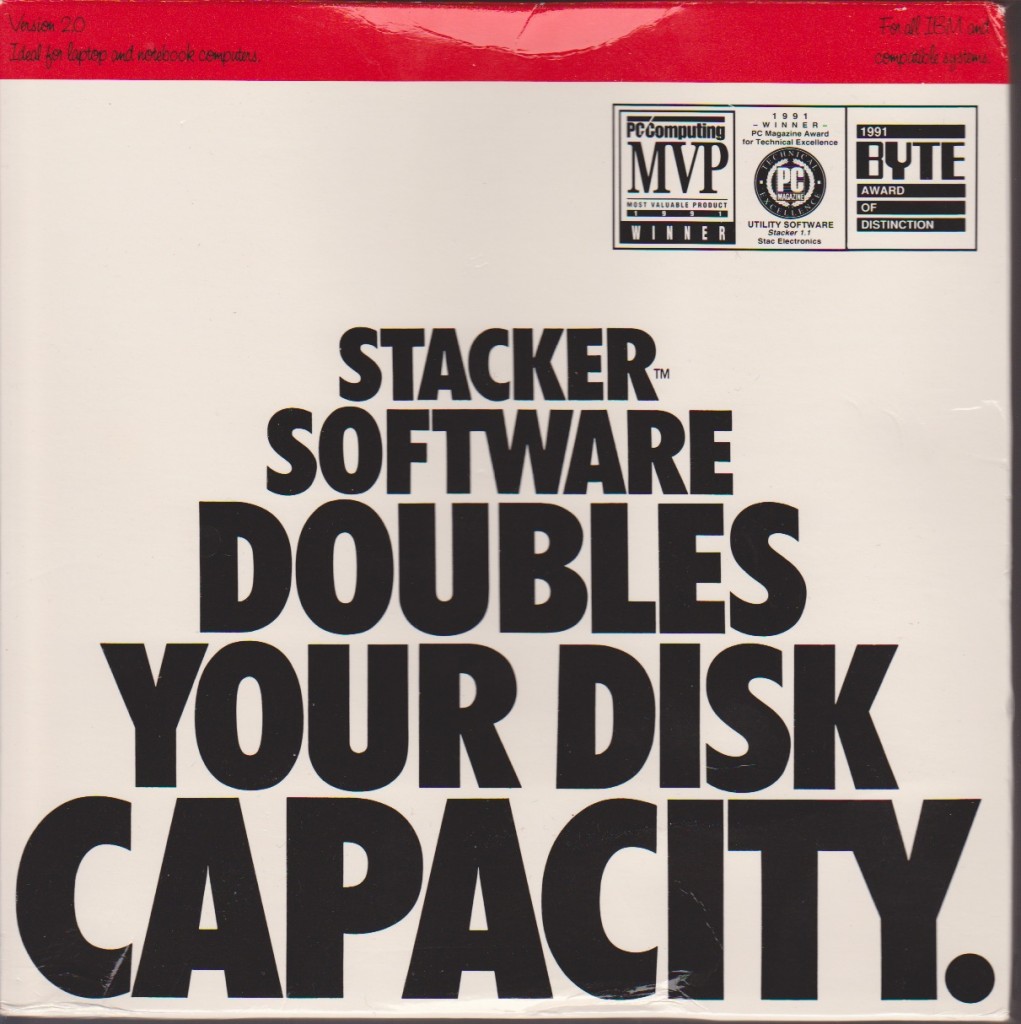

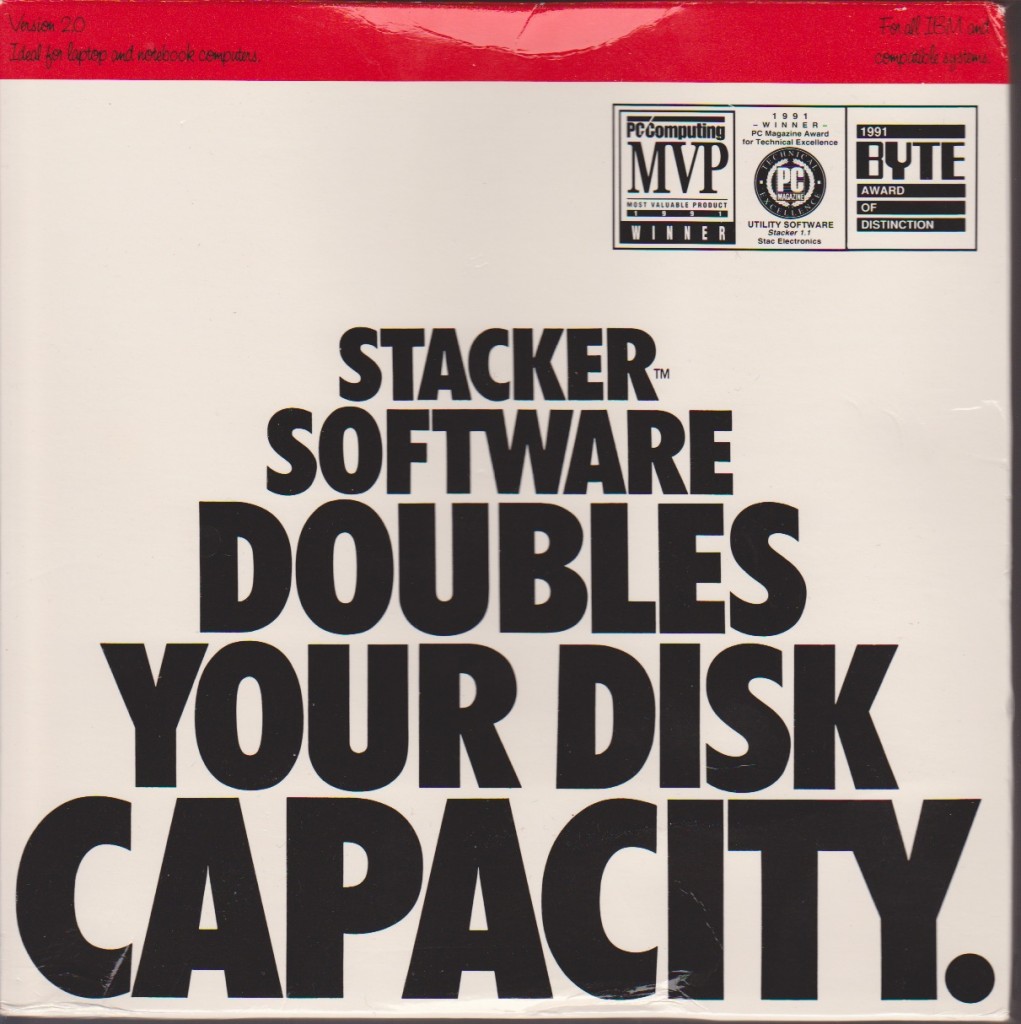

Until I saw this:

Stacker 2.0

Stacker changed everything for me, now via software compression not only could I fit 40+MB worth of crap on my 20MB disk, but I could even get more data on my floppies! The best part about stacker, unlike pack/zoo/pkzip and friends is that the compression was transparent. Meaning you load the driver, and pickup a new driver letter for the compressed volume, and from that point onward everything you do to that disk is compressed. All MS-DOS programs work with it. Yes really from Windows 3.0, to dbase, BBS packages, even pkzip (although it’ll get a 1:1 compression)

Stacker for OS/2

So for a long while life was good with Stacker although like everything else, things changed. I wasn’t going to run MS-DOS forever, and when I switched to OS/2 I was saddened to find out that there was no support for OS/2. Also Linux support was not going to happen either. Although they did eventually bring out a version for OS/2 it did not support HPFS volumes, only FAT.

And as you can see while Warp was the main target it could function with OS/2 2.0 and 2.1 as long as you had updated them to the latest fixpacks. And preferably installed the OS onto a FAT partition as the setup process hinges on it being able to modify the config.sys & boot directories from a DR-DOS boot floppy included in the package.

One of those funny things about disk compression is that for very heavy disk access programs that tend to compress pretty good (say databases with lots of text records) is that compression can greatly speed them up. If you are getting 16:1 compression (ie you have LOTS of spaces…) you only have to read the hard disk 1/16th as you would on an uncompressed volume. It’s still true to this day, although people tend to think disk compression added a significant amount of overhead to your computer (I never noticed) it can make some things faster.

Another thing that STAC was involved in was selling compression coprocessors.

Stac co-processor ad

While I’m not aware of these cards being that big of a seller, It is interesting to note that these co-processors were also available for other platforms namely the cisco router platform. Since people were using 56kb or less links, the idea of taking STAC’s LZS compression and applying it to the WAN was incredible! Imagine if you were printing remotely and suddenly if you got even a 4:1 boost in speed, suddenly things are usable! The best part is that while there were co-processors cisco also supplied the software engine in the IOS. Enabling it was incredibly easy too:

interface serial0/0

compress-stac

And you were good to go. The real shame today is that hardly anyone uses serial interfaces so the compression has basically ‘gone away’. Cisco did not enable it for Ethernet interfaces as those are ‘high speed’… Clearly they didn’t foresee that people would one day get these infuriating slow “high speed” internet connections being handed off on Ethernet and how compressing them would make things all the better.

I think the general thrust has been to a ‘black box’ approach that can cache files in the data stream, provide compression and QoS all in one.

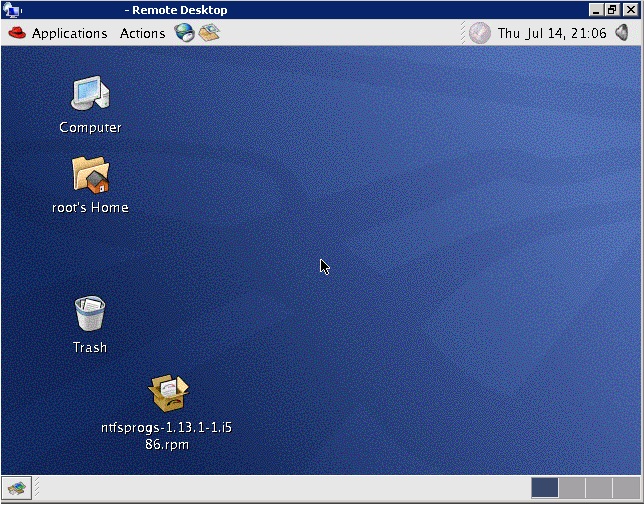

So until I re-install OS/2 on a FAT disk, let’s run this through the Windows 3.0 Synchronet BBS I was playing with.

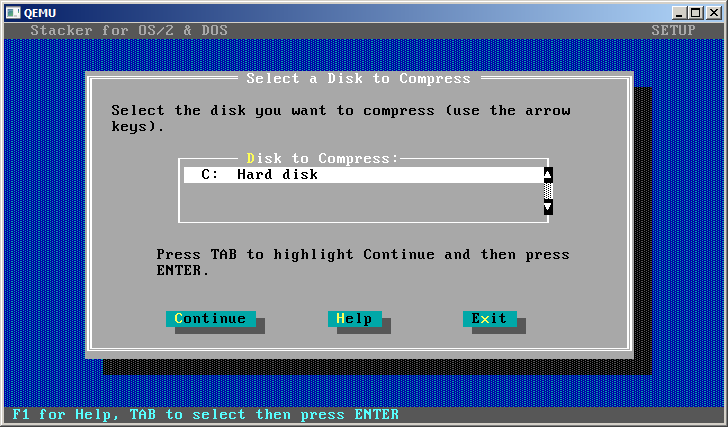

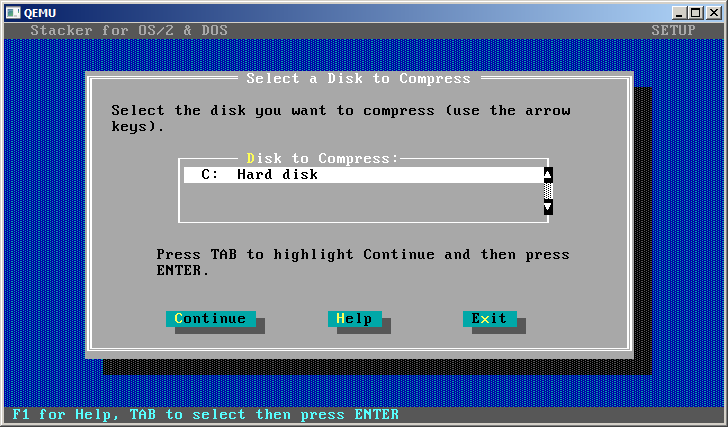

Stacker starts up with some ascii art of a growing hard disk. Maybe one day I’ll figure out how to dump Qemu’s video into something to make animated GIFs with. Until then… well.

Setup is pretty straight forward, pick a disk to compress, then decide if you’ll do the whole disk and incorporate the drive swapping fun, or just do the free space to create a sub volume, and manually manage it. I’m not in the mood to reconfigure anything so I’ll do what most people did and compress the whole drive. What is kind of fun to note, is that in modern implementations of compress & encryption you have to select one or the other you cannot do both. However using emulators that can support encrypted disks, you *could* then compress from within. I don’t know why the new stuff doesn’t let you, maybe the layered containers gets too much. But I do bet there is something out there for Windows that’ll mount a file as a disk image (like Windows 7 can mount VHD’s) on an encrypted volume, then turn on compression…….

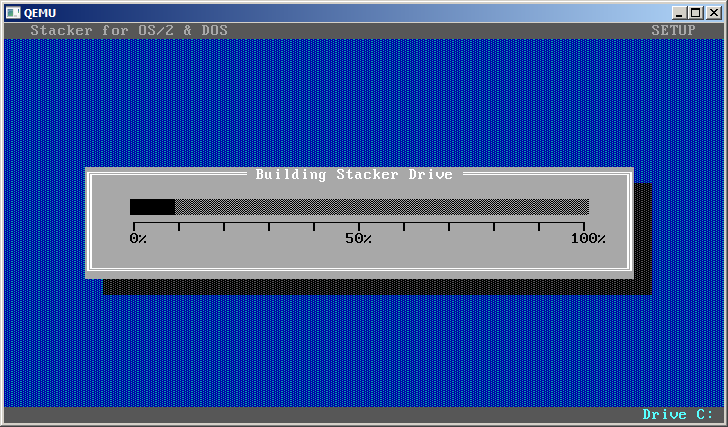

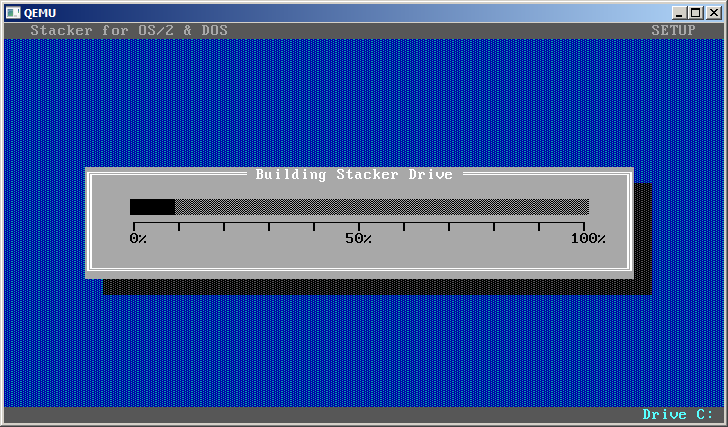

Anyways with the target selected, it will then copy the files, then create the volume…

Which took a minute, then it’ll defrag the disk using Norton Speed disk (from that point onward it seems that speed disk disappears..?)

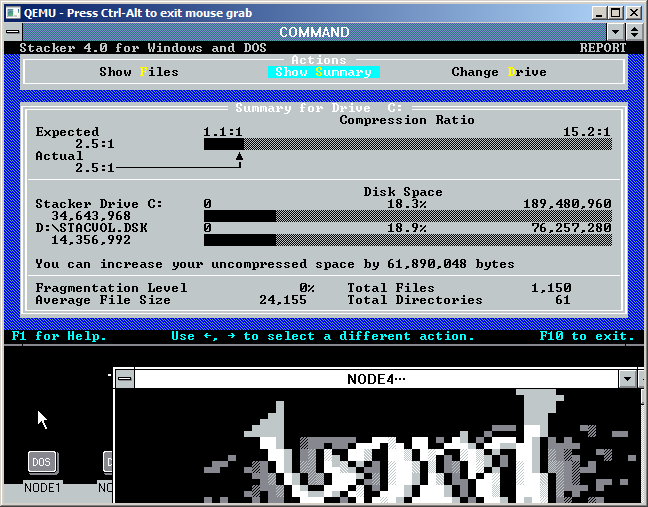

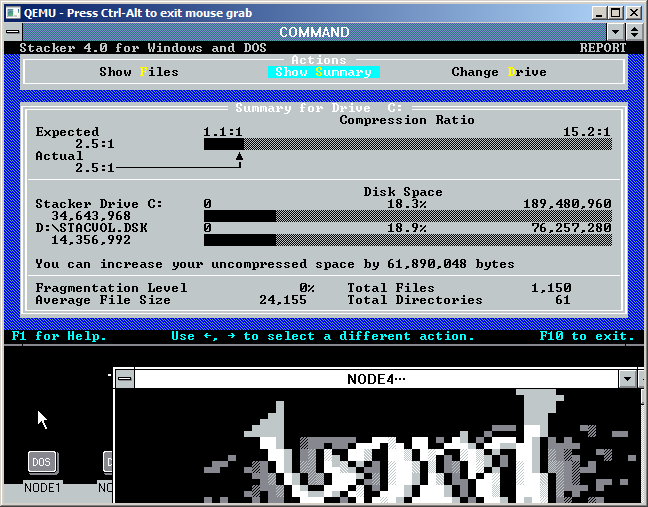

And once that is done, we are basically good to go. So how did it do on my 80MB ‘test’ disk?

I’d have to say pretty good, 2.5:1 is pretty snazzy! And my BBS is working, I didn’t have to change a single line, it’s 100% transparent.

Eventually IDE hard disks took over the world, and got larger capacities, faster and cheaper. Not to mention the world was switching operating systems from MS-DOS to Windows 95, or Windows NT and STAC just got out of the market after the big lawsuit.

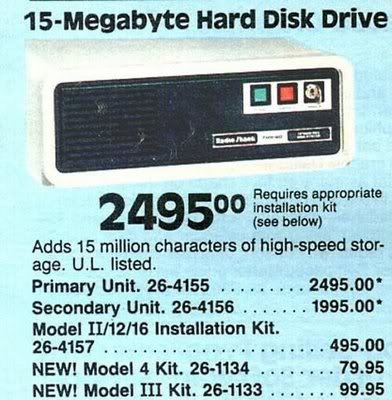

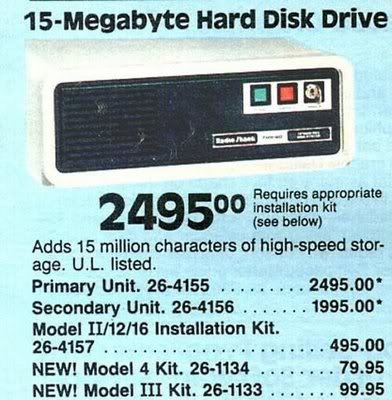

But it’s funny looking at old disk ads… And what a catastrophic thing it was to fill the things up.

But it’s funny looking at old disk ads… And what a catastrophic thing it was to fill the things up.

But before then, we had stacker…