I had originally planned on doing this for the 4th of July, but something happened along the way. I had forgotten that this is 1995, not 2024, and things were a little bit different back then.

Back in the early days of the internet, when Al Gore himself had single handedly created it out of the dirt, The idea of address space exhaustion didn’t loom overhead as it did in the late 00s. And in those days getting public addresses was a formality. It was a given that not only would the servers all have public TCP/IP addresses, but so would the clients. Protocols like FTP would open ports not only from client to server, but also server to client. This was also the case for RealAudio. Life was good.

The problem with trying to build anything with this amazing technology is that while I do have a public address for the server, it’s almost a given that YOU are not directly connected to the internet. Almost everyone these days uses some kind of router that’ll implement Network Address Translation (NAT), allowing for countless machines to sit behind a single registered address, and map their connections in and out behind one address. For protocols like FTP, they have to be built to watch and dynamically add these ports. FTP is popular, RealAudio is not. So, the likelihood of anyone actually being able to connect to a RealAudio 1.0 server is pretty much nil.

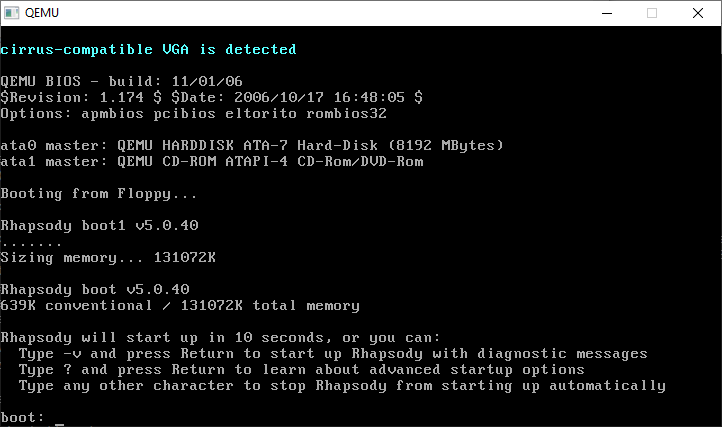

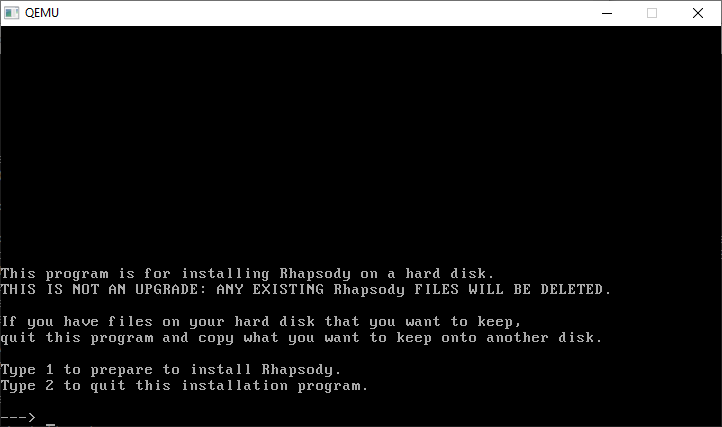

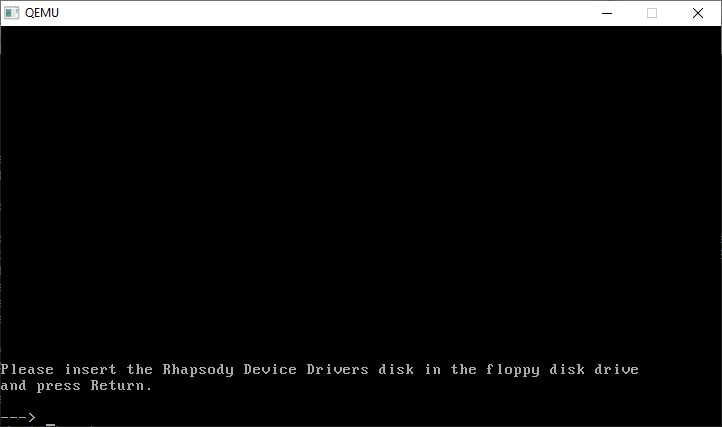

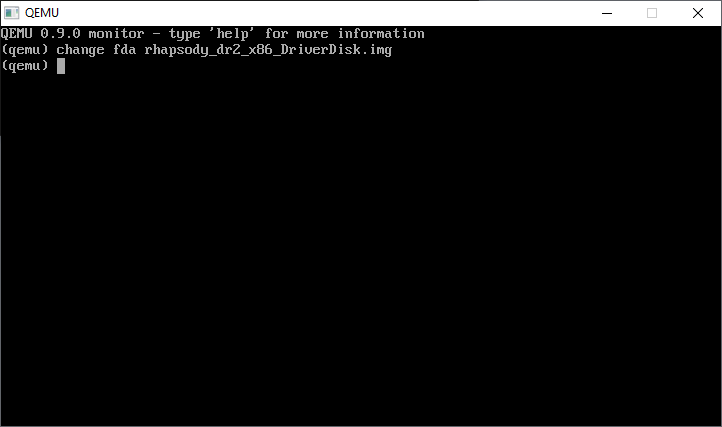

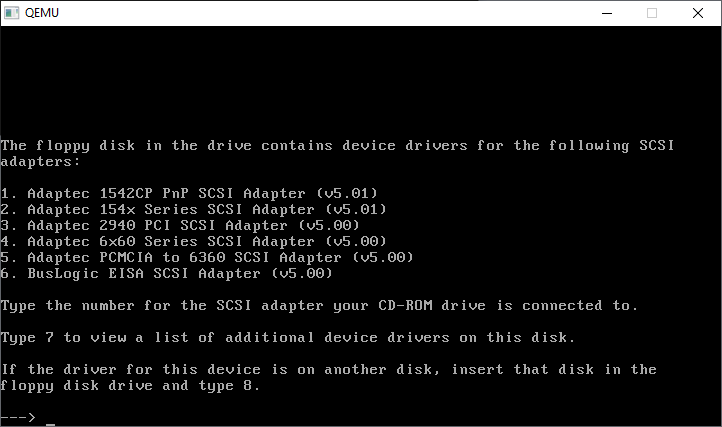

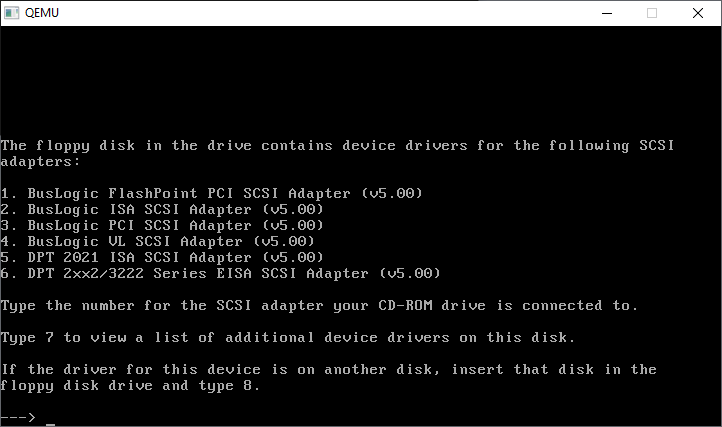

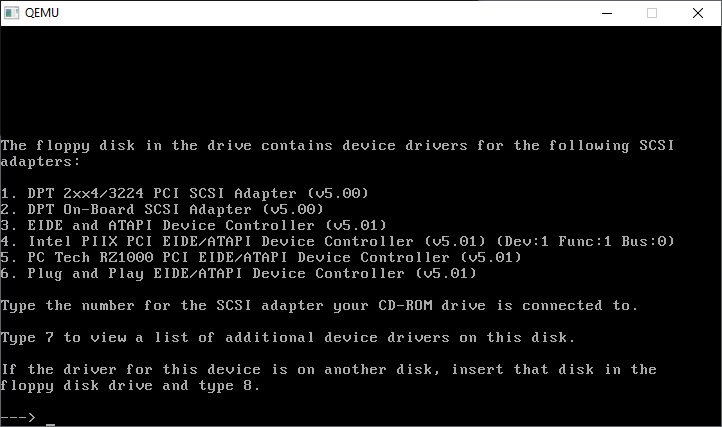

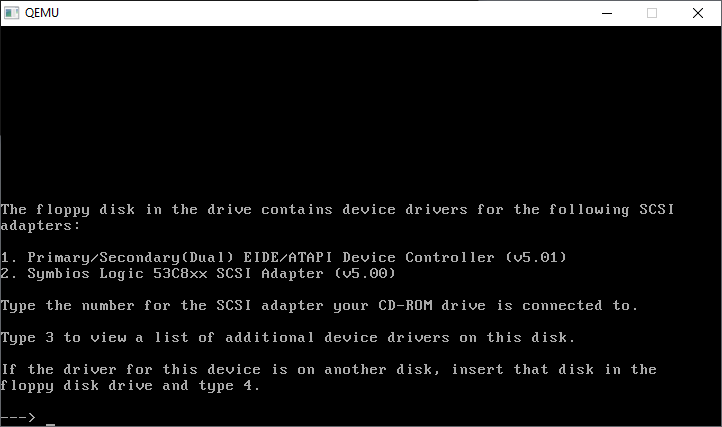

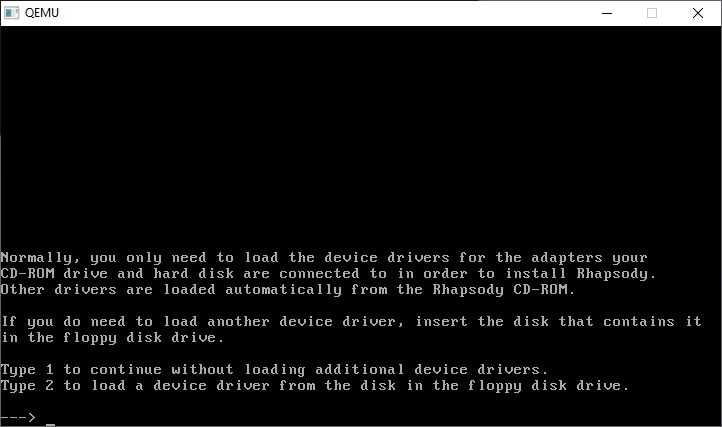

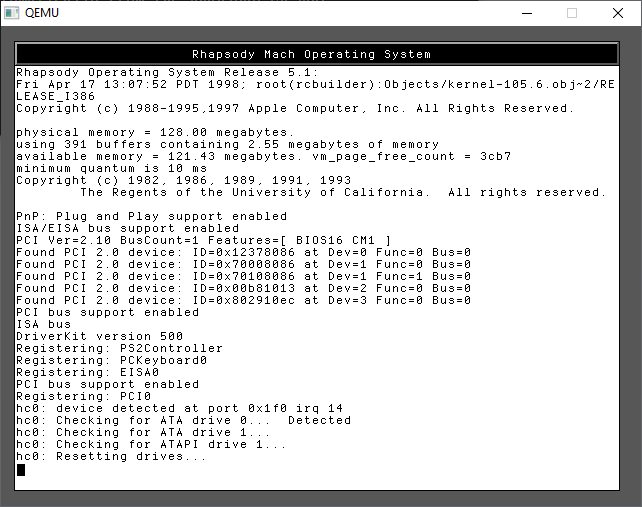

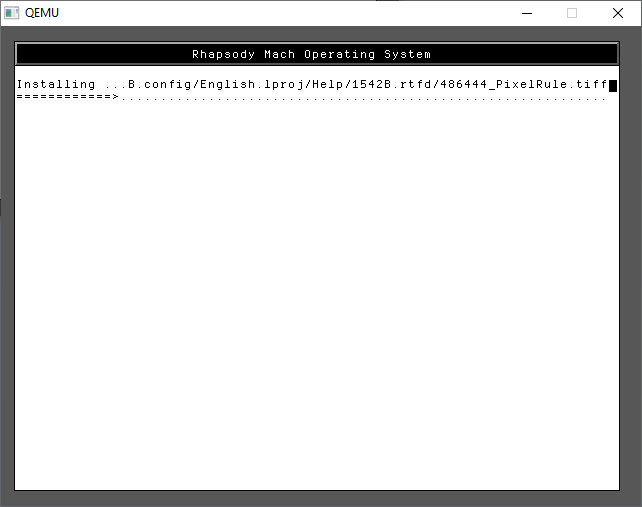

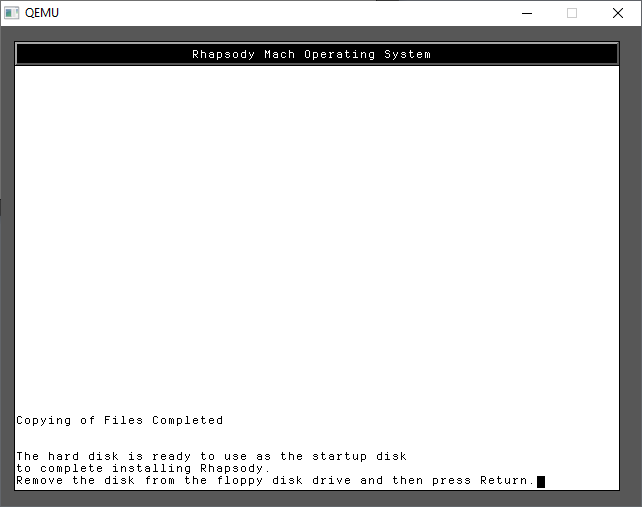

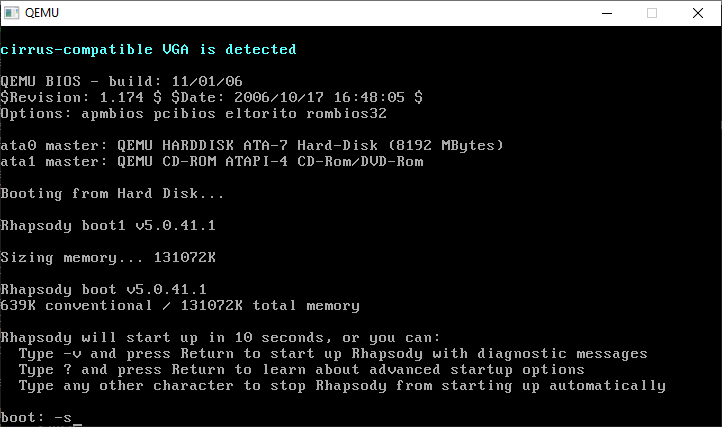

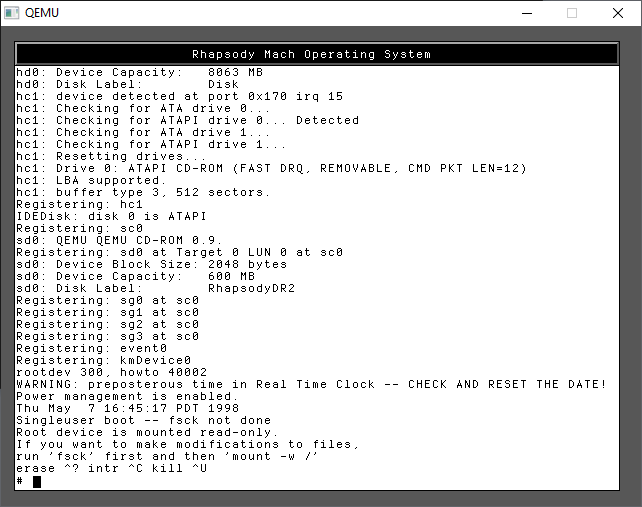

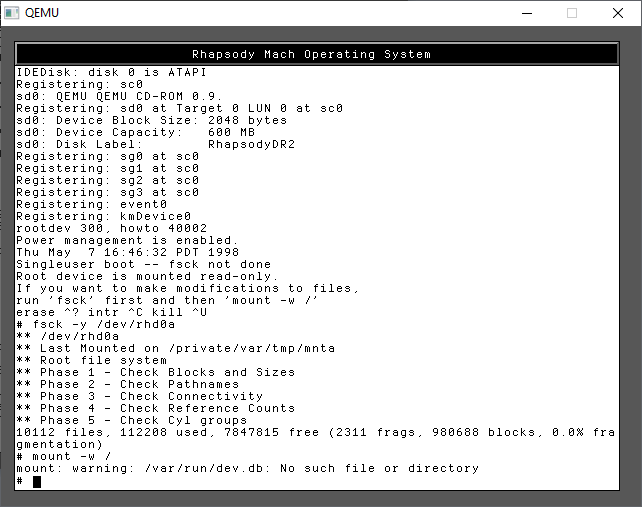

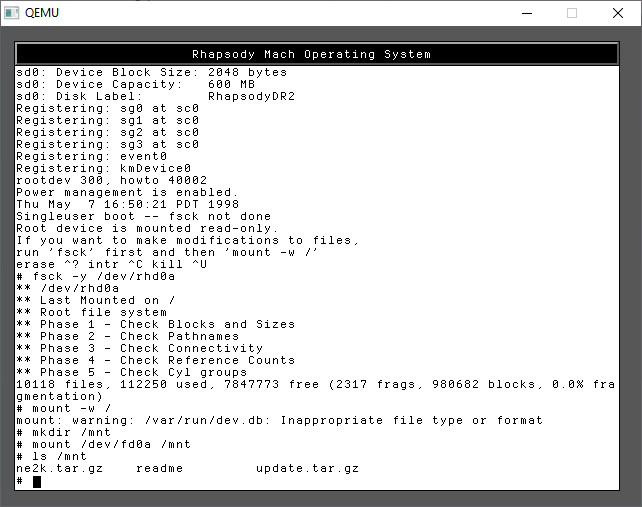

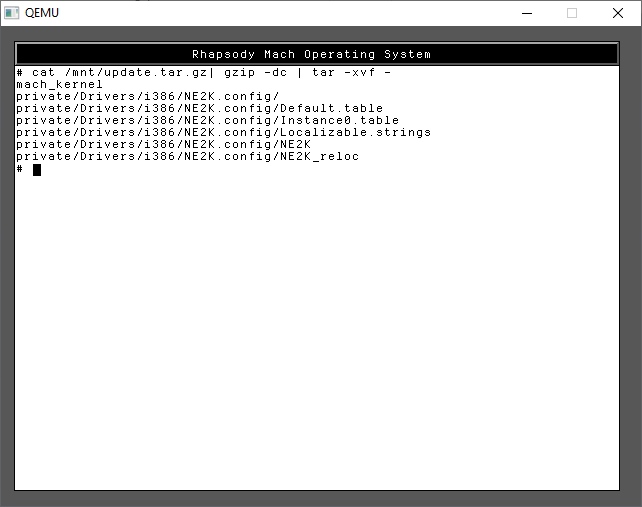

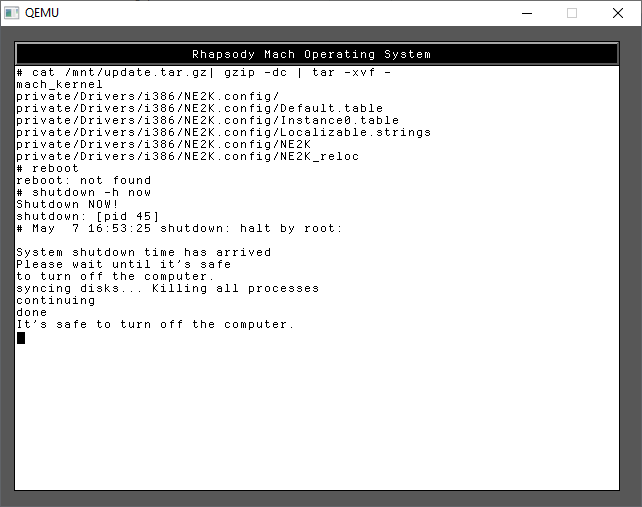

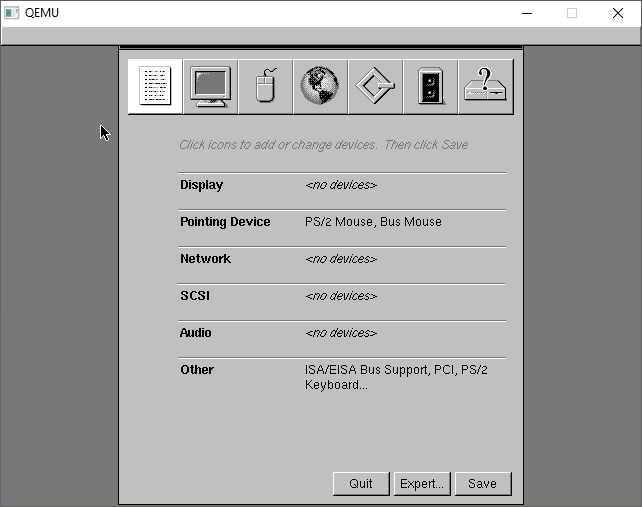

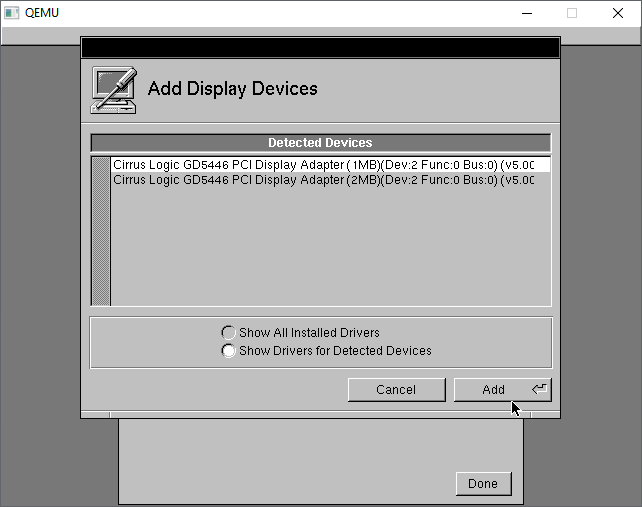

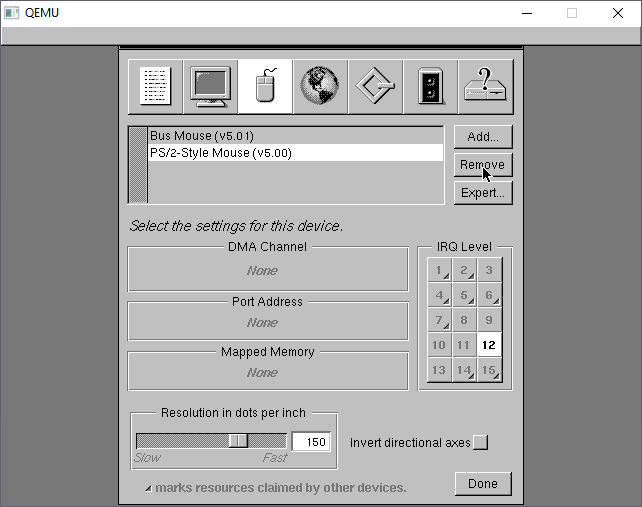

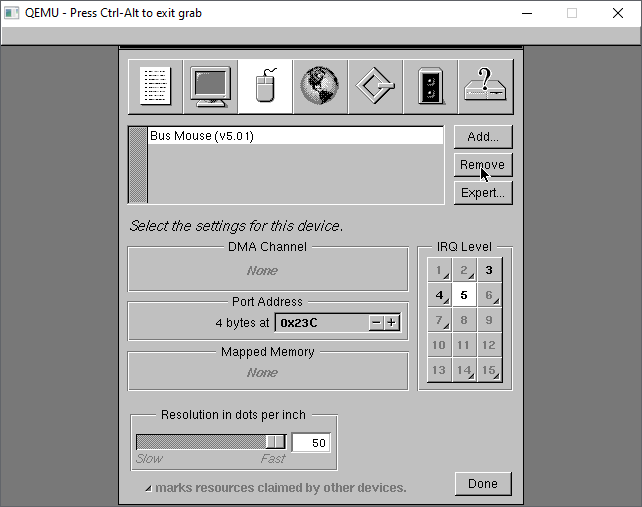

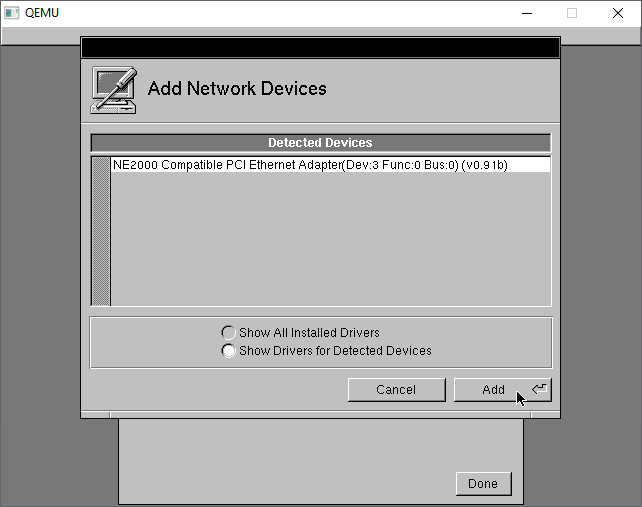

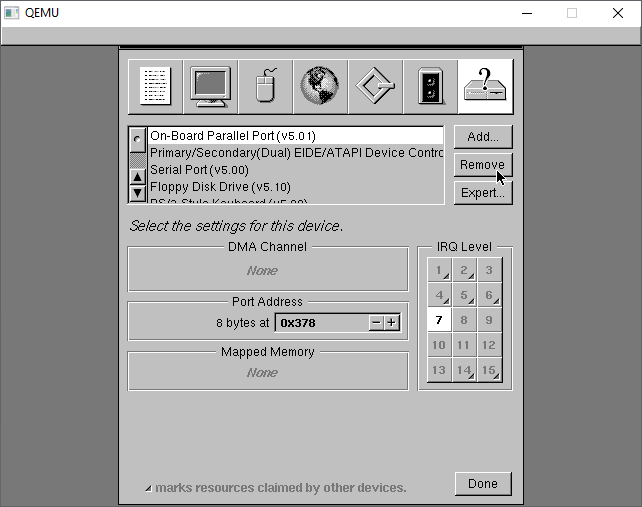

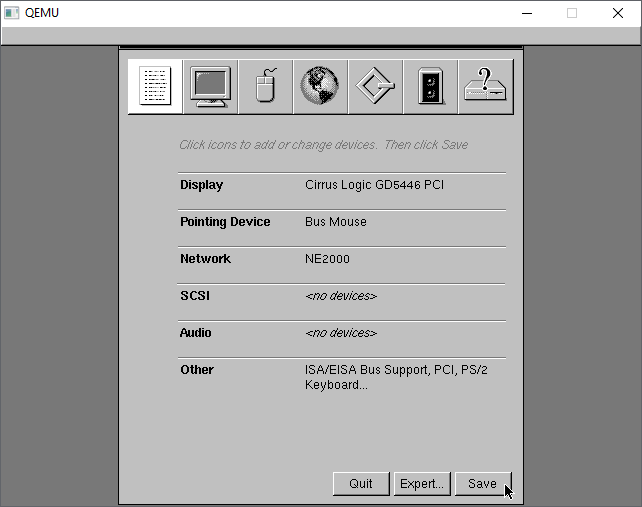

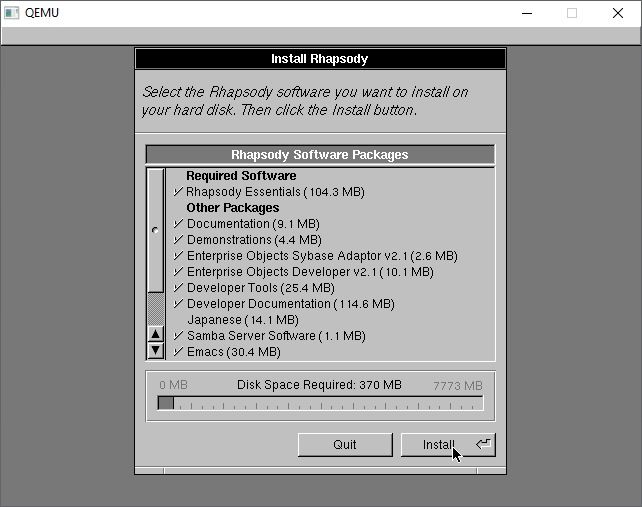

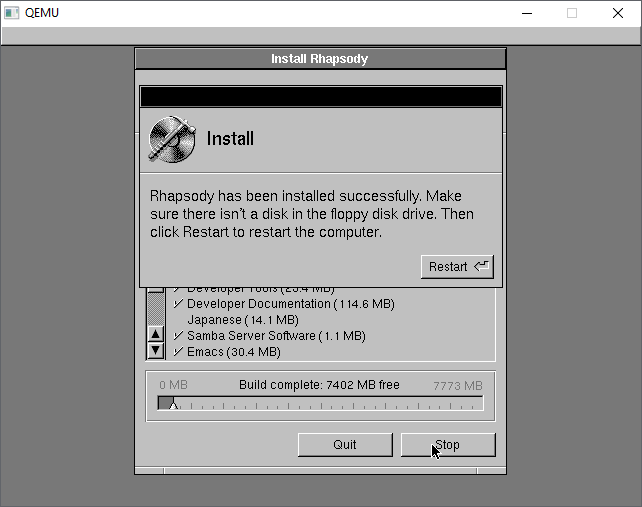

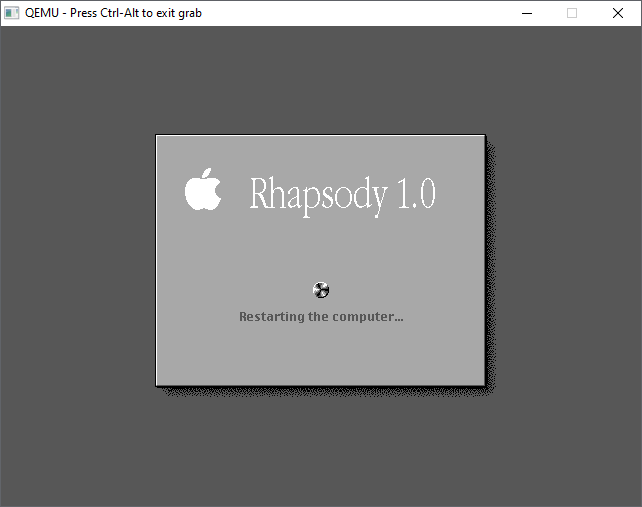

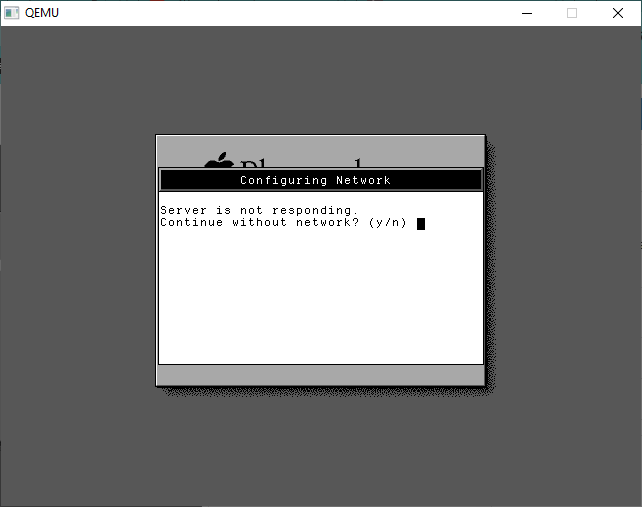

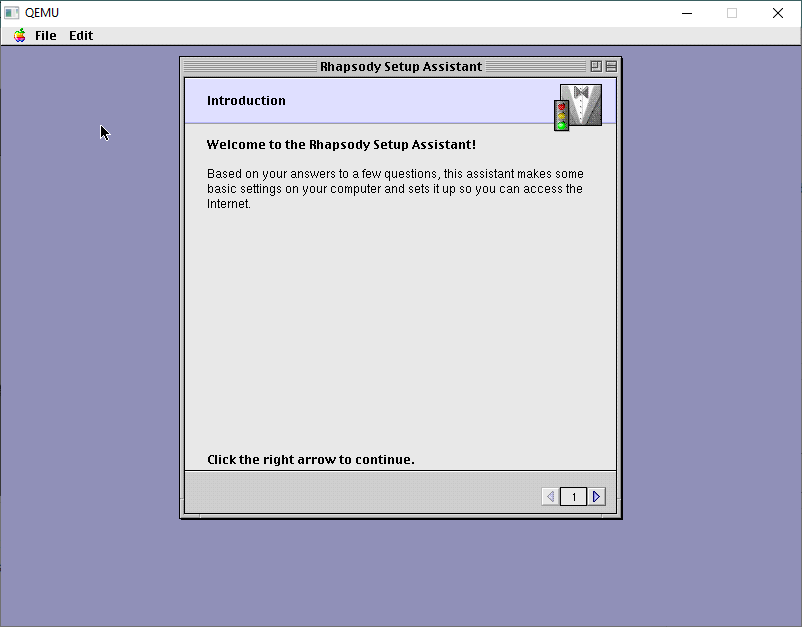

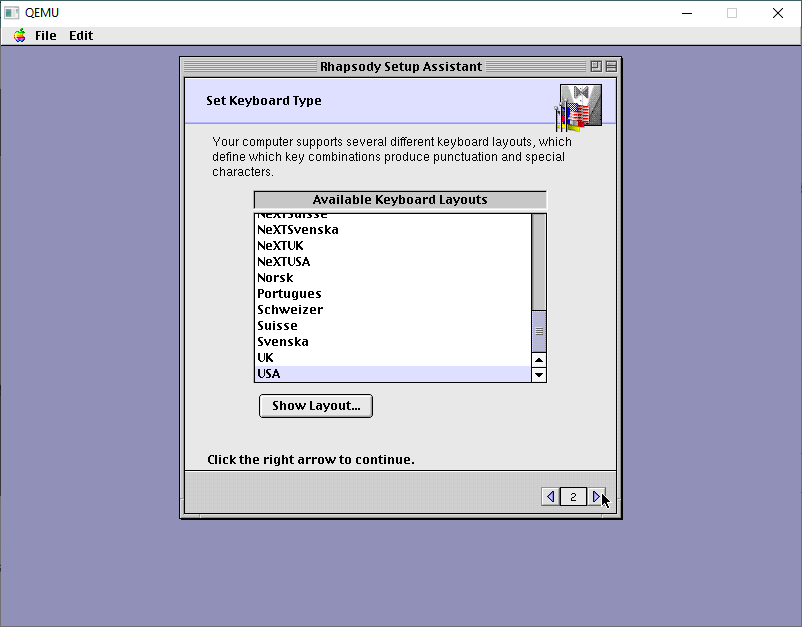

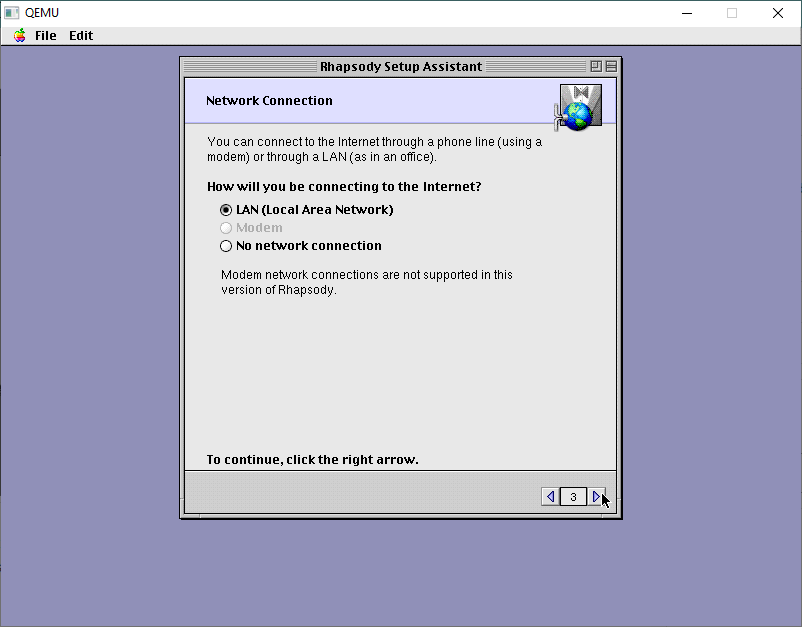

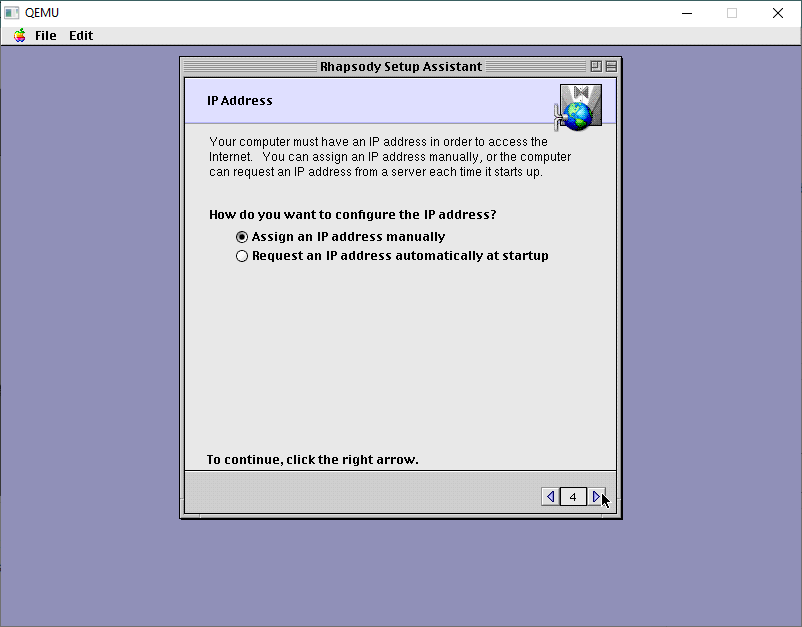

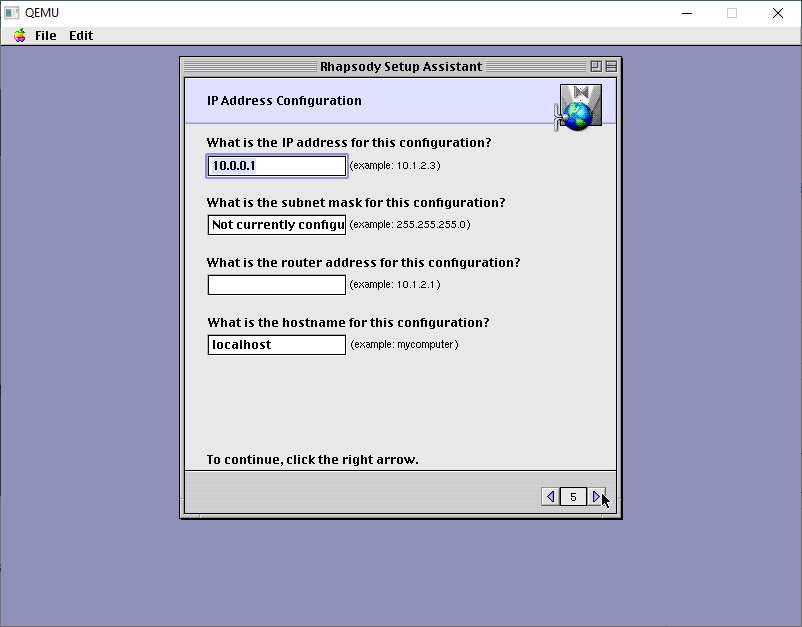

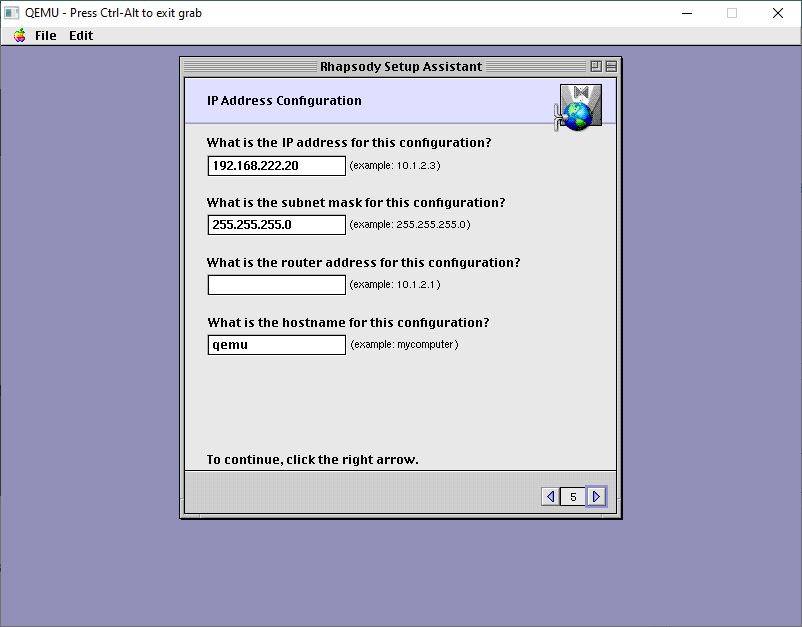

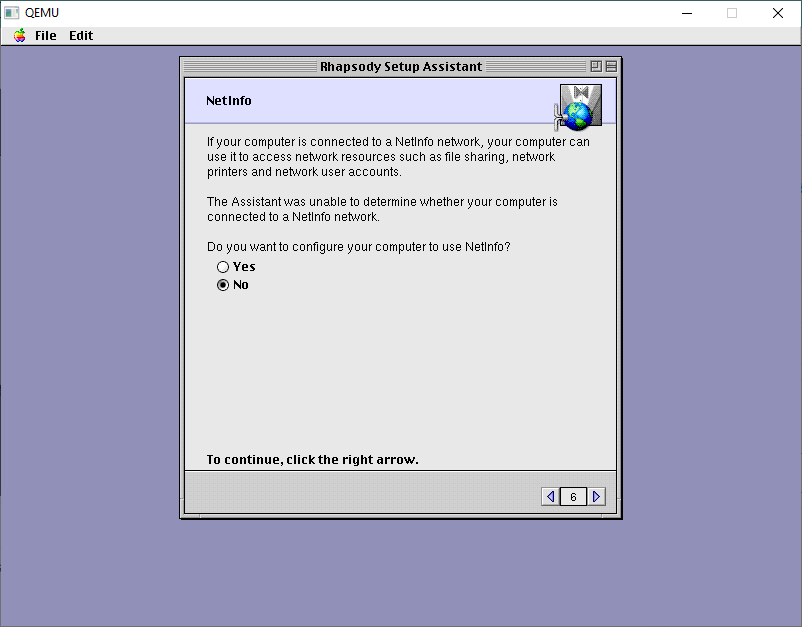

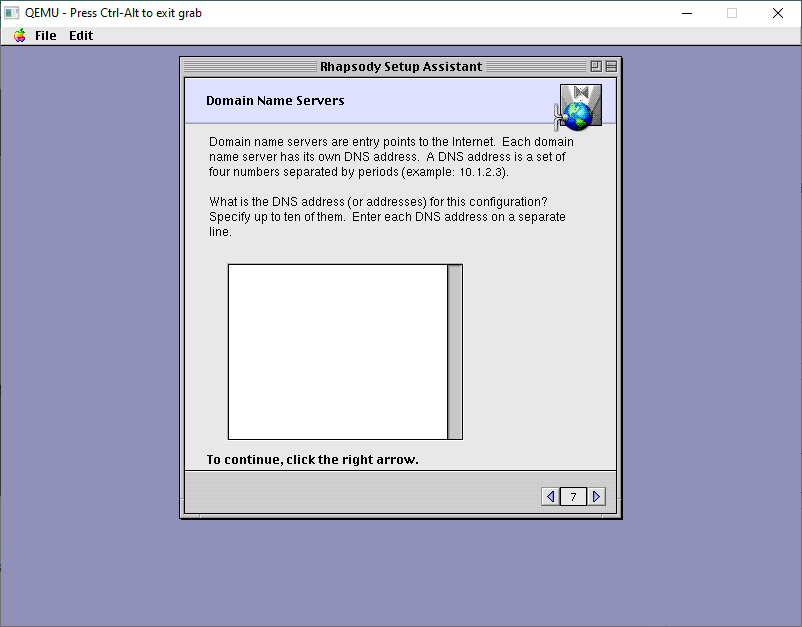

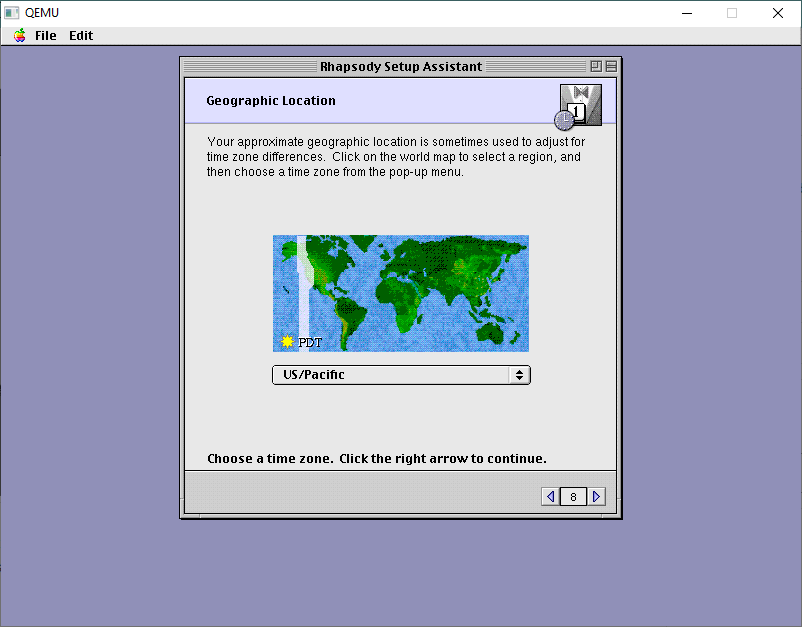

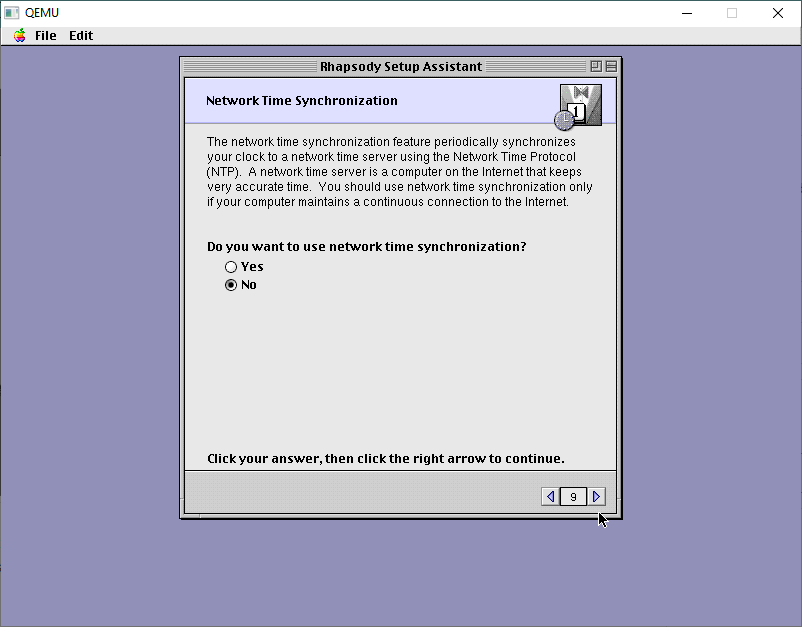

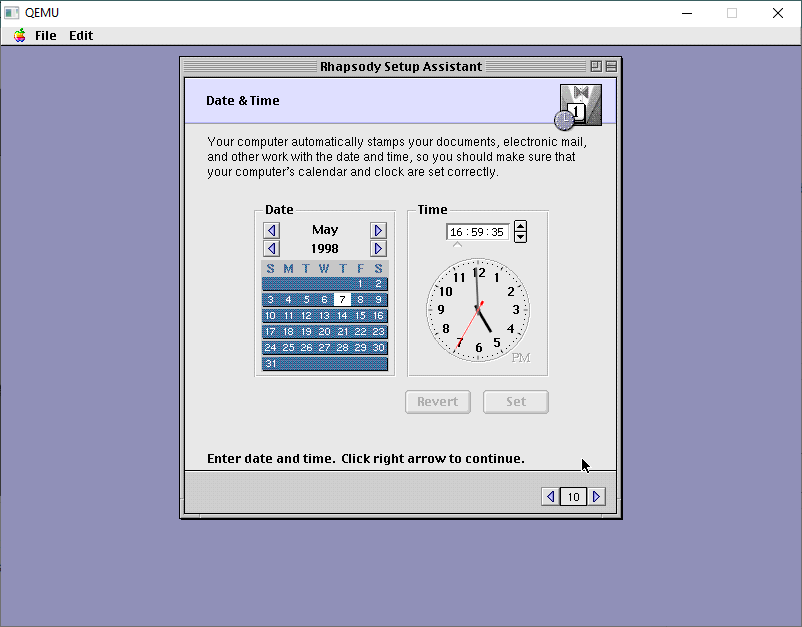

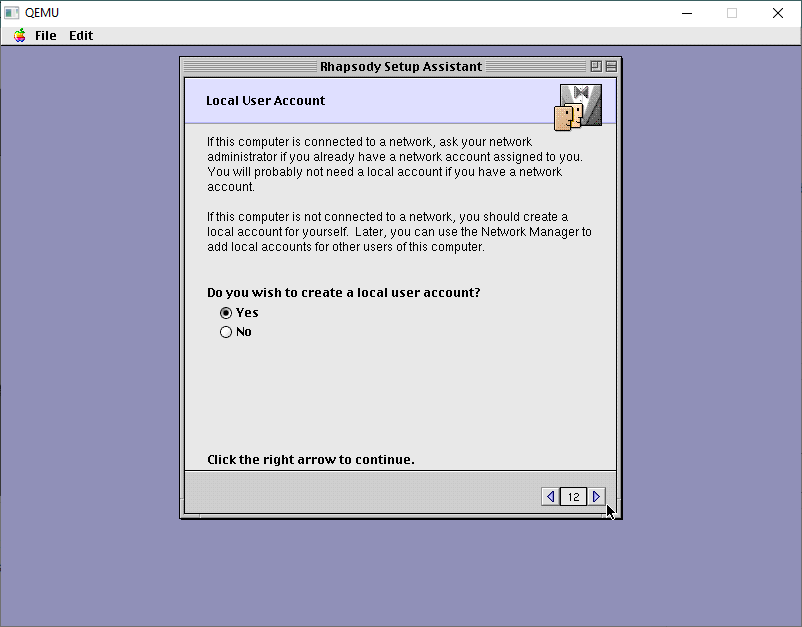

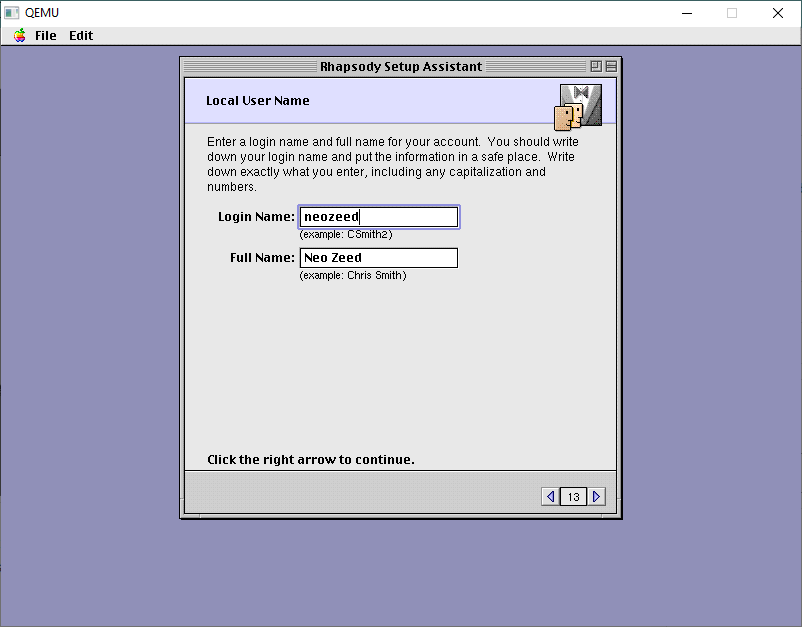

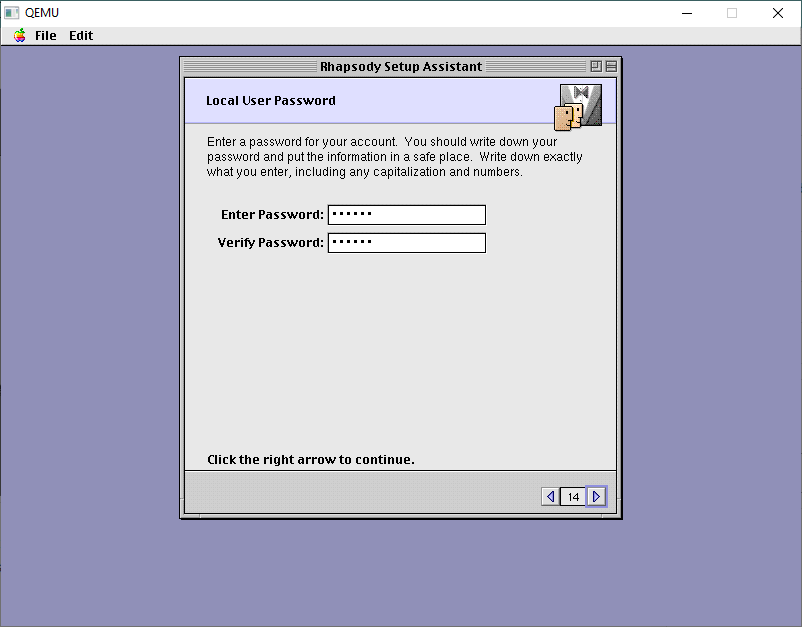

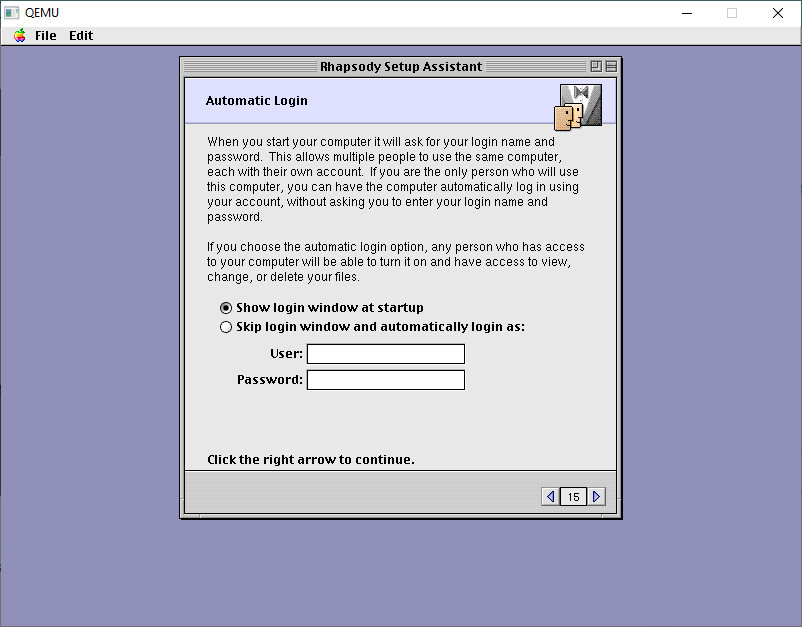

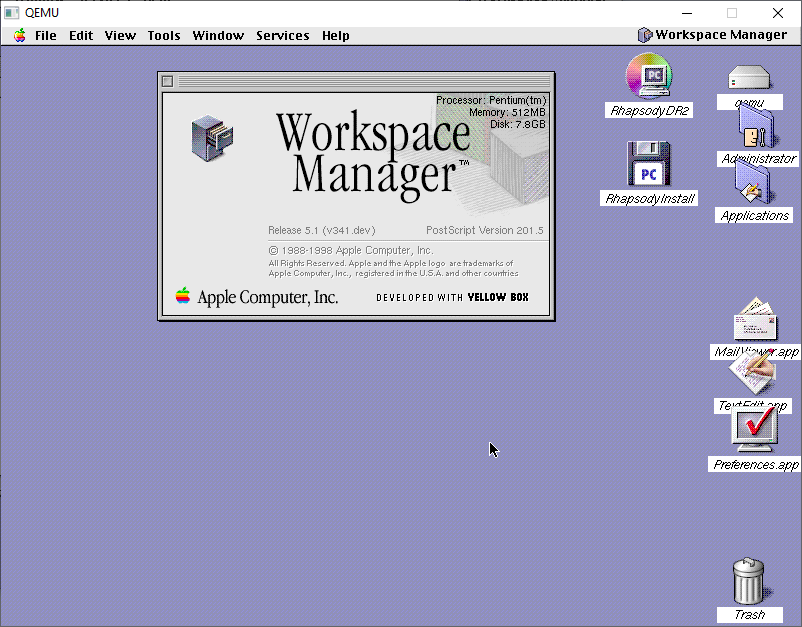

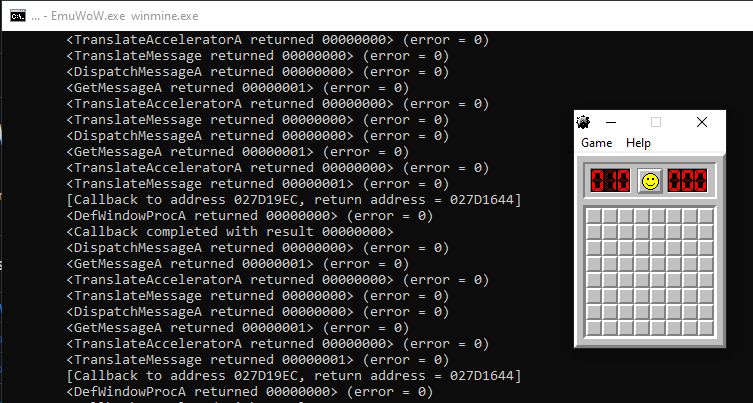

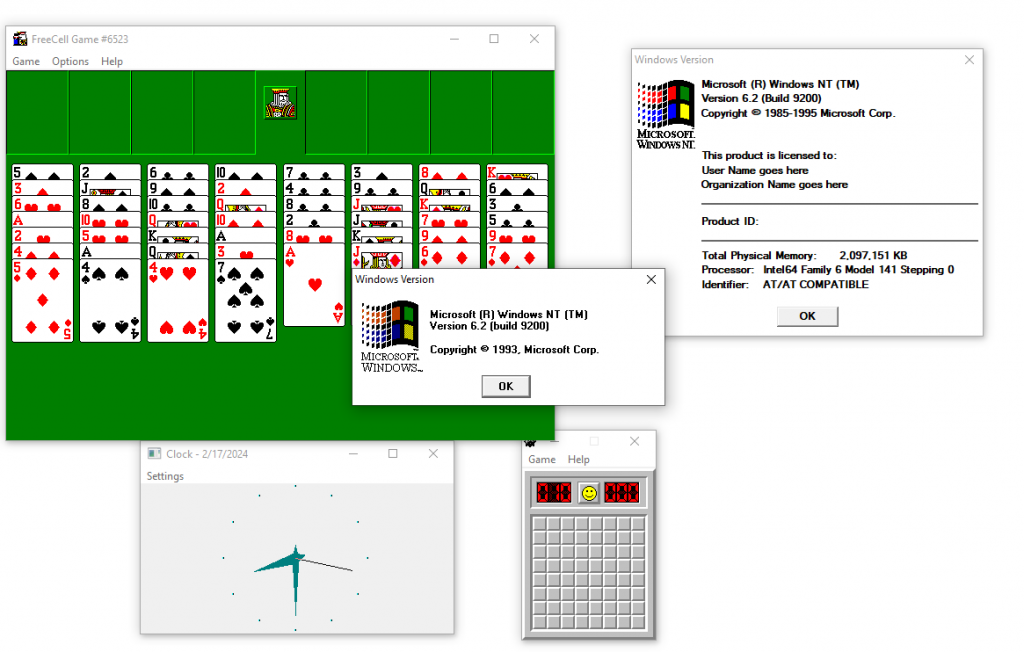

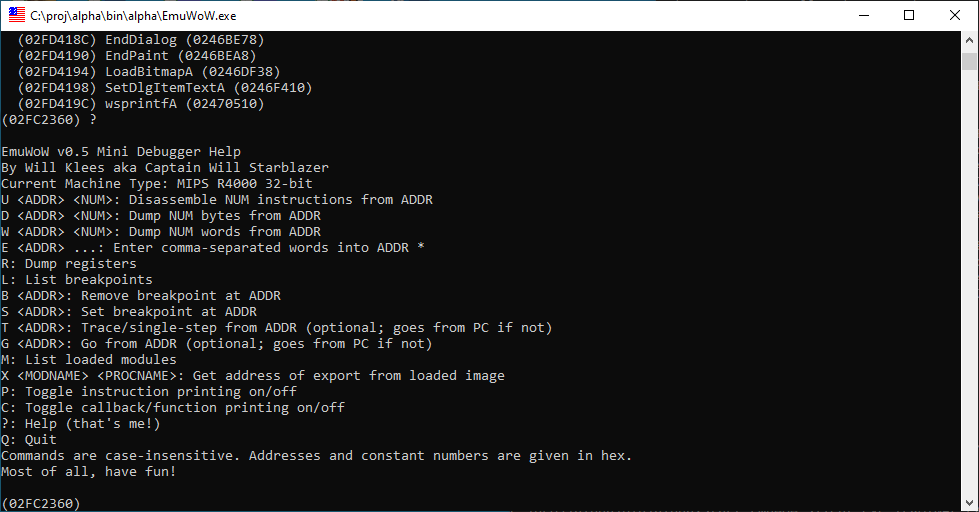

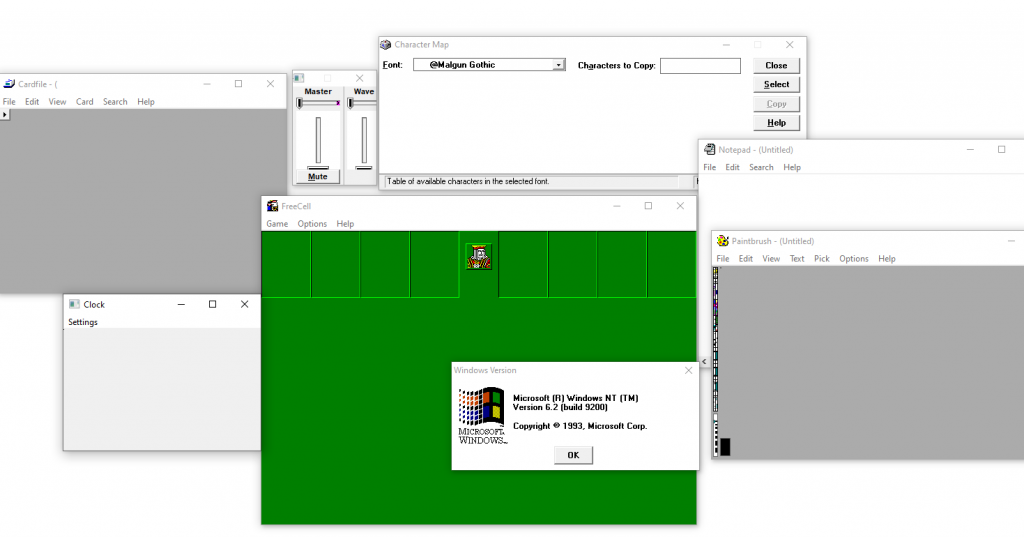

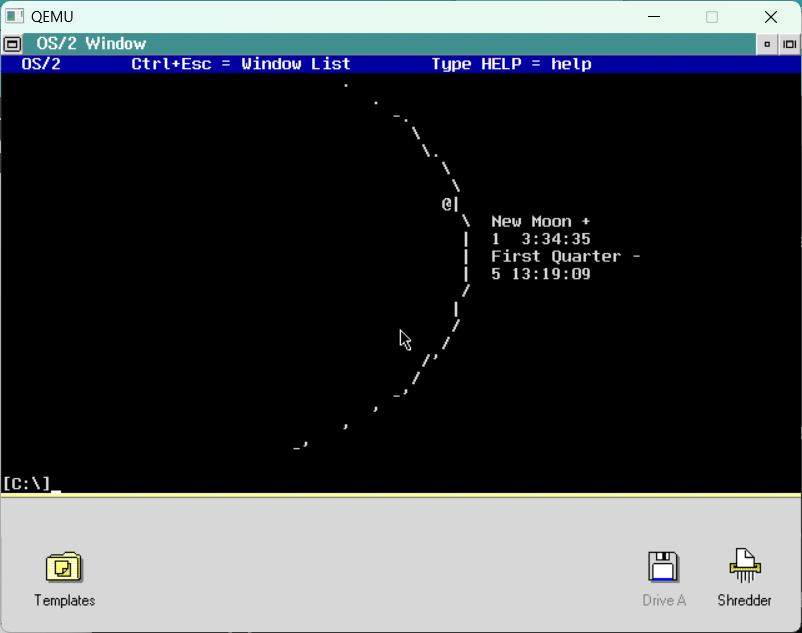

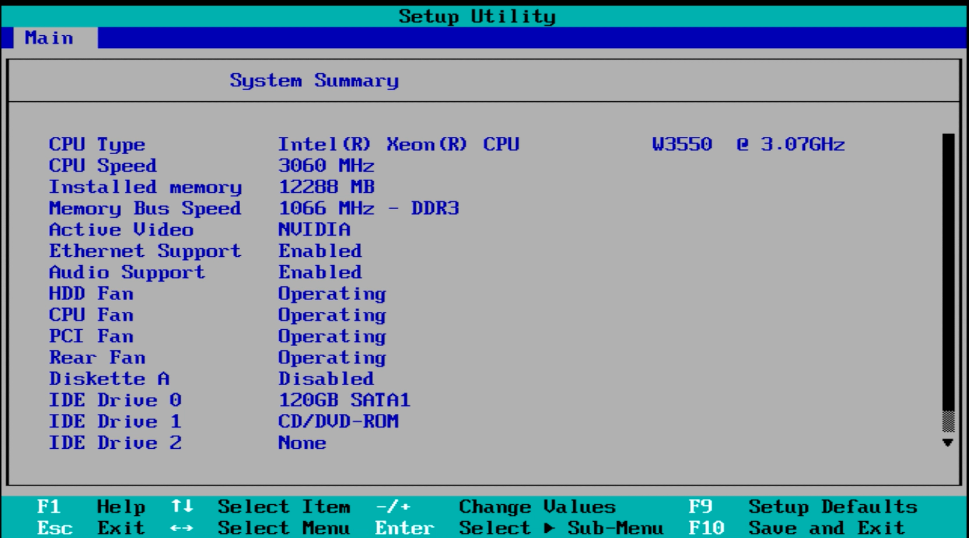

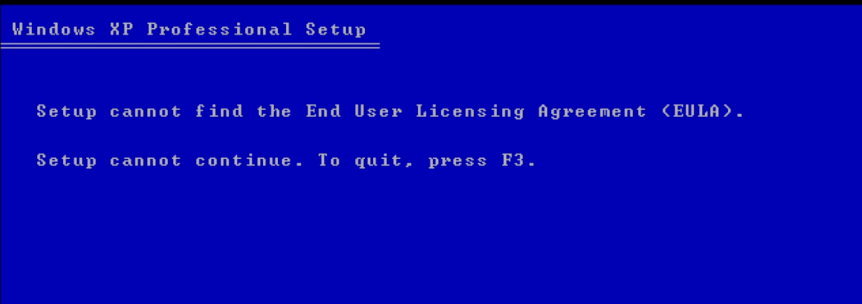

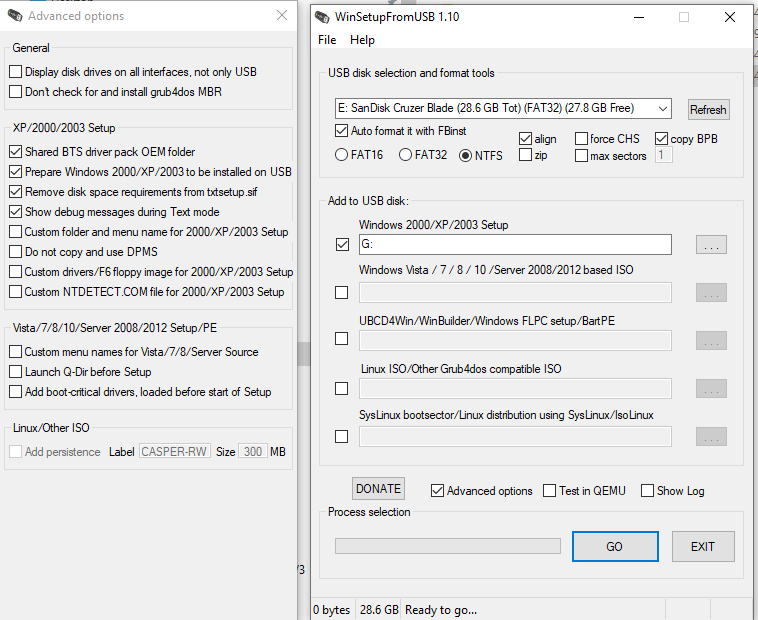

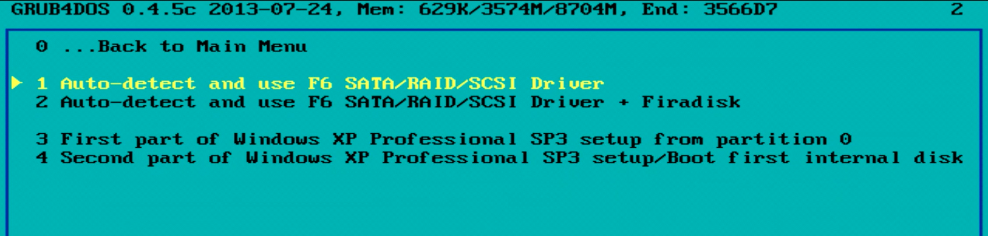

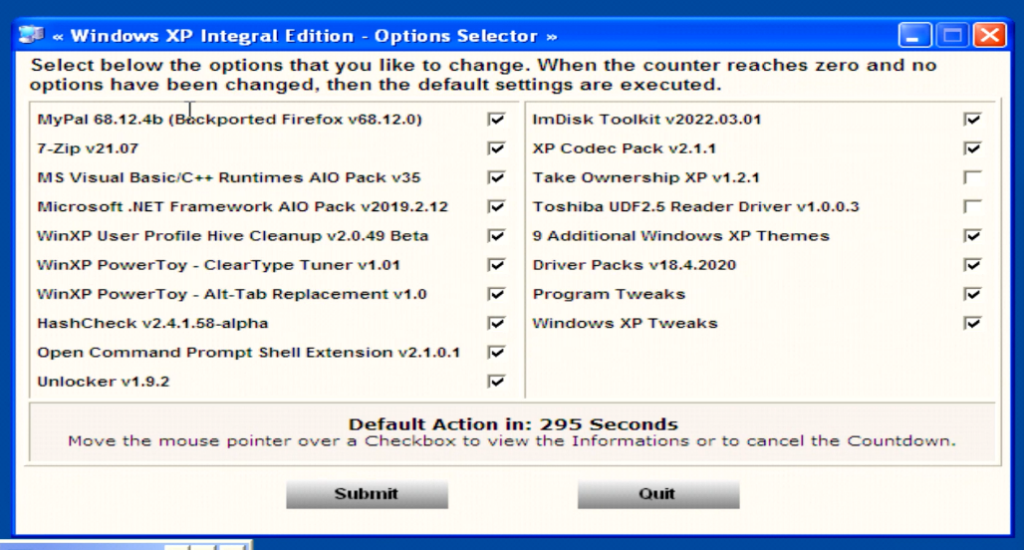

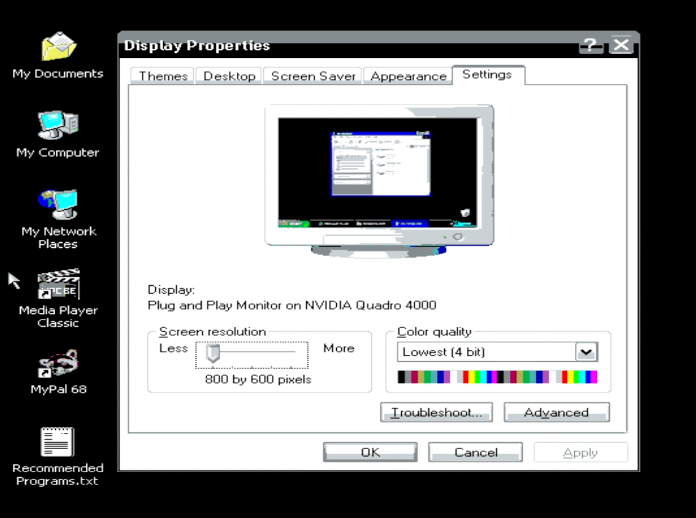

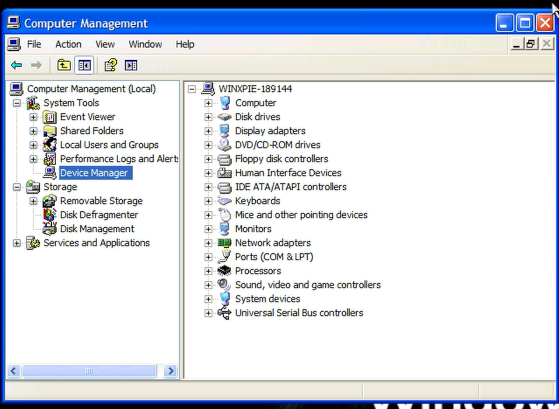

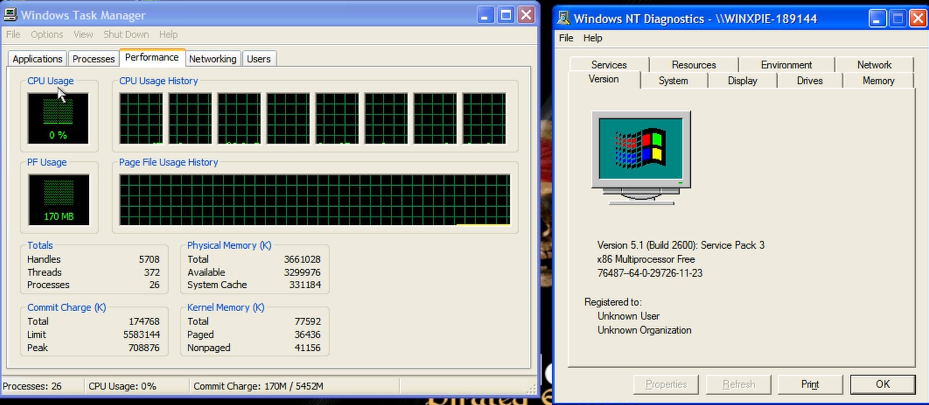

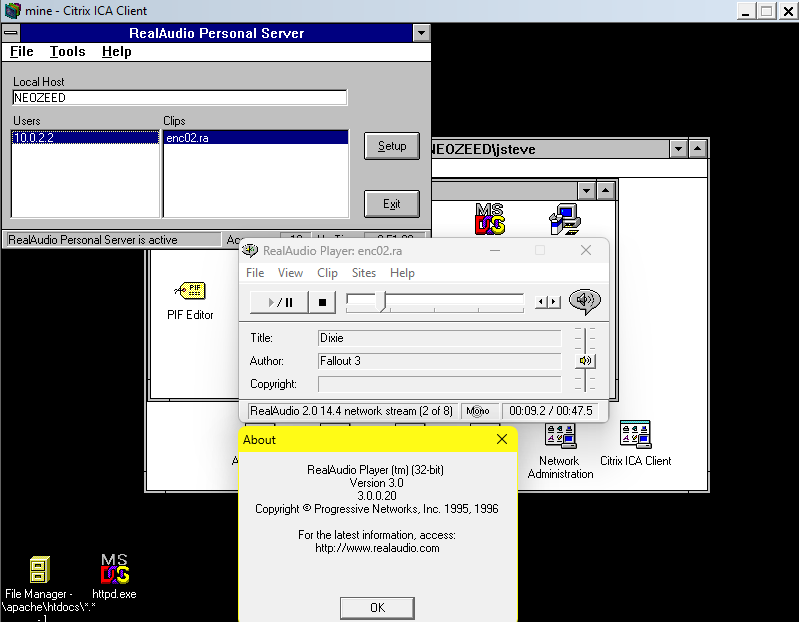

The software is pretty easy to find on archive.org, (mirrored). Since it’s very audio centric, I decided to install the server onto a Citrix 1.8 server using Qemu 0.9. I had gone with this, as the software is hybrid 16bit/32bit and I need a working sound card, and I figured the Citrix virtual stuff is good enough.

First thing first, you need some audio to convert. Thankfully in modern terms ripping or converting is trivial unlike the bad old days. First off, I needed a copy of the Enclave radio, and I found that too on archive.org. The files are all in mp3 format, but the RealAudio encoder wants to work with wav files. The quickest way I could think of was to use ffmpeg.

ffmpeg -i Enclave Radio - Battle Hymn of the Republic.mp3 -ar 11025 -ab 8k -ac 1 enc01.wavThis converts the mp3 into an 11Khz mono wav file. It’s something the encoder can work with. Another nice thing about Citrix is how robust it can use your local drives, cutting out the whole part of moving data in & out of the VM.

One thing about how RealAudio works is that first there is the ability to load up a .ram or playlist file. In this case, I took the ‘enclave playlist’ from Fallout 3, and made a simple playlist as enclave.ram:

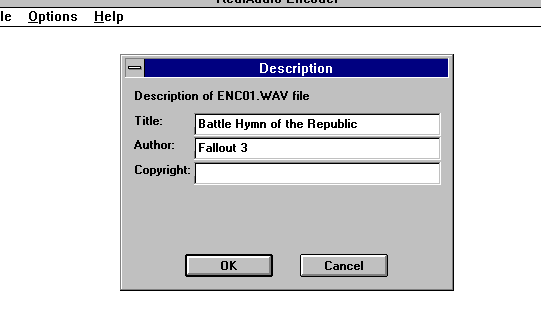

The encoder allows for some metadata to be set. Nothing too big.

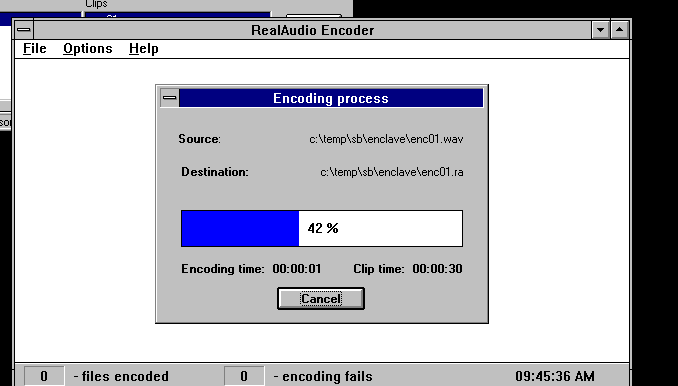

And then it thankfully takes my i7 seconds to convert this, even under emulation, using a shared drive. And import option to deselect is to enable playback in real-time, as it’ll never work as it cannot imagine a world in which the processor is substantially faster than the encoder.

Converting the 8 files took a few minutes, and then I had my RealAudio 1.0 data.

Next up is to create a .RAM or playlist.

pnm://localhost/enc01.ra

pnm://localhost/enc02.ra

pnm://localhost/enc03.ra

pnm://localhost/enc04.ra

pnm://localhost/enc05.ra

pnm://localhost/enc06.ra

pnm://localhost/enc07.ra

pnm://localhost/enc08.ra

The playlist should be served via HTTP, and I had just elected to use an old hacked up Apache to run on NT 3.1. As it only has to serve some simple files.

The scene is all set, the RealAudio player pulls the playlist from Apache, then it connects on TCP port 7070 of the RealAudio server to identify itself and get the file metadata. Then the RealAudio server then opens a random UDP port to the client and sends the stream, as the client updates the server via UDP of how the stream is working. And this is where it all breaks down, as there is not going to be any nice way to handle this UDP connection from the server to the client.

Well, this was disappointing.

In a fit of rage, I then tried to see if ffmpeg could convert the real audio into FLAC so you could hear the incredible drop in quality, and as luck would have it, YES it can! To concatenate them, I used a simple list file:

file ENC01.RA

file ENC02.RA

file ENC03.RA

file ENC04.RA

file ENC05.RA

file ENC06.RA

file ENC07.RA

file ENC08.RAAnd then the final command:

ffmpeg -f concat -safe 0 -i list.txt Enclave_v1.flacAnd thanks to ‘modern’ web standards, you can now listen to this monstrosity!

This takes about 10MB of WAV audio derived from 8MB of MP3’s, and converted down to 472kb worth of RealAudio. Converting that back to a 4.4MB FLAC file.

To keep in mind what network ports are needed at a minimum it’s the following:

- TCP 1494 * Citrix

- TCP 7070 * RealAudio

- UDP 7070 * RealAudio (statistics?)

- TCP 80 * Apache

And of course, it seems to limit the RealAudio server to the client in the 7000-7999 range but that is just my limited observation. This works find at home on a LAN where the server is using SLiRP as the host TCP/UDP ports appear accessible from 10.0.2.2, while giving the server a free-standing IP also works better, but again it needs that 1:1 conversation greatly limiting it in today’s world.

Also, as pointless as it sounds, you can play the real audio files from the Citrix server for extra audio loss.

Personally, things could have gone a lot better on the 3rd of July, I thought I’d escaped but got notified on the 5th they forgot about me. Oh well Happy 4th for everyone else.