The following is a guest post by NCommander of SoylentNews fame!

For those who’ve been long-time readers of SoylentNews, it’s not exactly a secret that I have a personal interest in retro computing and documenting the history and evolution of the Personal Computer. About three years ago, I ran a series of articles about restoring Xenix 2.2.3c, and I’m far overdue on writing a new one. For those who do programming work of any sort, you’ll also be familiar with “Hello World”, the first program most, if not all, programmers write in their careers.

A sample hello world program might look like the following:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

printf("Hello world\n");

return 0;

}

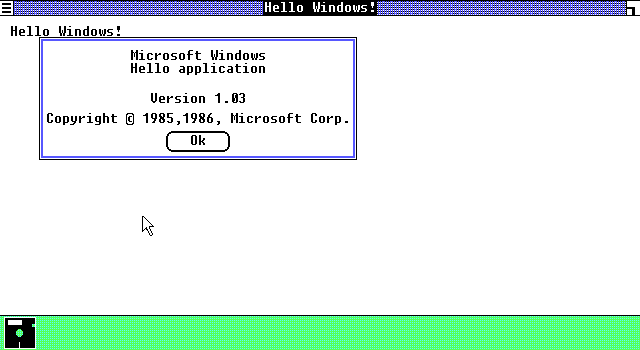

Recently, I was inspired to investigate the original HELLO.C for Windows 1.0, a 125 line behemoth that was talked about in hush tones. To that end, I recorded a video on YouTube that provides a look into the world of programming for Windows 1.0, and then testing the backward compatibility of Windows through to Windows 10.

For those less inclined to watch a video, my write-up of the experience is past the fold and an annotated version of the file is available on GitHub (https://github.com/NCommander/win1-hello-world-annotations)

Bring Out Your Dinosaurs – DOS 3.3

Before we even get into the topic of HELLO.C though, there’s a fair bit to be said about these ancient versions of Windows. Windows 1.0, like all pre-95 versions, required DOS to be pre-installed. One quirk however with this specific version of Windows is that it blows up when run on anything later than DOS 3.3. Part of this is due to an internal version check which can be worked around with SETVER. However, even if this version check is bypassed, there are supposedly known issues with running COMMAND.COM. To reduce the number of potential headaches, I decided to simply install PC-DOS 3.3, and give Windows what it wants.

You might notice I didn’t say Microsoft DOS 3.3. The reason is that DOS didn’t exist as a standalone product at the time. Instead, system builders would license the DOS OEM Adaptation Kit and create their own DOS such as Compaq DOS 3.3. Given that PC-DOS was built for IBM’s own line of PCs, it’s generally considered the most “generic” version of the pre-DOS 5.0 versions, and this version was chosen for our base. However, due to its age, it has some quirks that would disappear with the later and more common DOS versions.

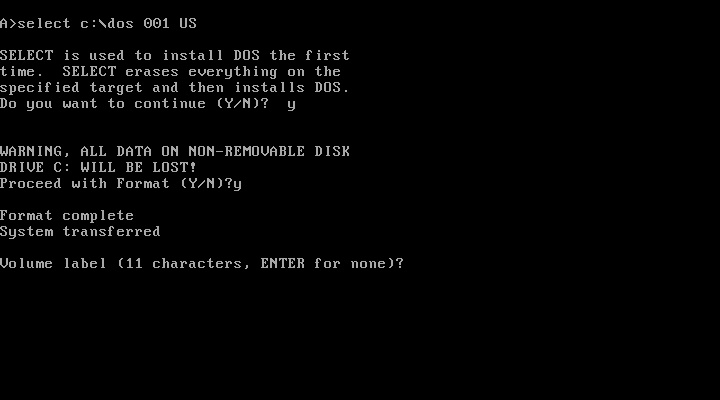

PC DOS 3.3 loaded just fine in VirtualBox and — with the single 720 KiB floppy being bootable — immediately dropped me to a command prompt. Likewise, FDISK and FORMAT were available to partition the hard drive for installation. Each individual partition is limited, however, to 32 MiB. Even at the time, this was somewhat constrained and Compaq DOS was the first (to the best of my knowledge) to remove this limitation. Running FORMAT C: /S created a bootable drive, but something oft-forgotten was that IBM actually provided an installation utility known as SELECT.

SELECT’s obscurity primarily lies in its non-obvious name or usage, nor the fact that it’s actually needed to install DOS; it’s sufficient to simply copy the files to the hard disk. However, SELECT does create CONFIG.SYS and AUTOEXEC.BAT so it’s handy to use. Compared to the later DOS setup, SELECT requires a relatively arcane invocation with the target installation folder, keyboard layout, and country-code entered as arguments and simply errors out if these are incorrect. Once the correct runes are typed, SELECT formats the target drive, copies DOS, and finishes installation.

Without much fanfare, the first hurdle was crossed, and we’re off to installing Windows.

Windows 1.0 Installation/Mouse Woes

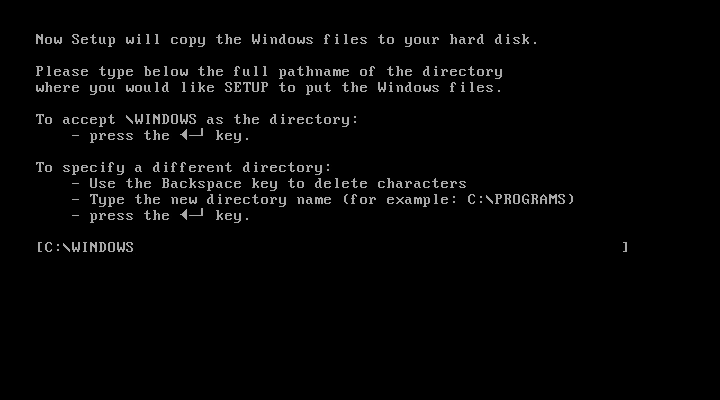

With DOS installed, it was on to Windows. Compared to the minimalist SELECT command, Windows 1.0 comes with a dedicated installer and a simple text-based interface. This bit of polish was likely due to the fact that most users would be expected to install Windows themselves instead of having it pre-installed.

Another interesting quirk was that Windows could be installed to a second floppy disk due to the rarity of hard drives of the era, something that we would see later with Microsoft C 4.0. Installation went (mostly) smoothly, although it took me two tries to get a working install due to a typo. Typing WIN brought me to the rather spartan interface of Windows 1.0.

Although functional, what was missing was mouse support. Due to its age, Windows predates the mouse as a standard piece of equipment and predates the PS/2 mouse protocol; only serial and bus mice were supported out of the box. There are two ways to solve this problem:

The first, which is what I used, involves copying MOUSE.DRV from Windows 2.0 to the Windows 1.0 installation media, and then reinstalling, selecting the “Microsoft Mouse” option from the menu. Re-installation is required because WIN.COM is statically linked as part of installation with only the necessary drivers included; there is no option to change settings afterward. The SDK documentation details the static linking process, and how to run Windows in “slow mode” for driver development, but the end result is the same. If you want to reconfigure, you need to re-install.

The second option, which I was unaware of until after producing my video is to use the PS/2 release of Windows 1.0. Like DOS of the era, Windows was licensed to OEMs who could adapt it to their individual hardware. IBM did in fact do so for their then-new PS/2 line of computers, adding in PS/2 mouse support at the time. Despite being for the PS/2 line, this version of Windows is known to run on AT-compatible machines.

Regardless, the second hurdle had been passed, and I had a working mouse. This made exploring Windows 1.0 much easier.

The Windows 1.0 Experience

If you’re interested in trying Windows 1.0, I’d recommend heading over to PCjs.org and using their browser-based emulator to play with it as it already has working mouse support and doesn’t require acquiring 35 year old software. Likewise, there are numerous write-ups about this version, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t spend at least a little time talking about it, at least from a technical level.

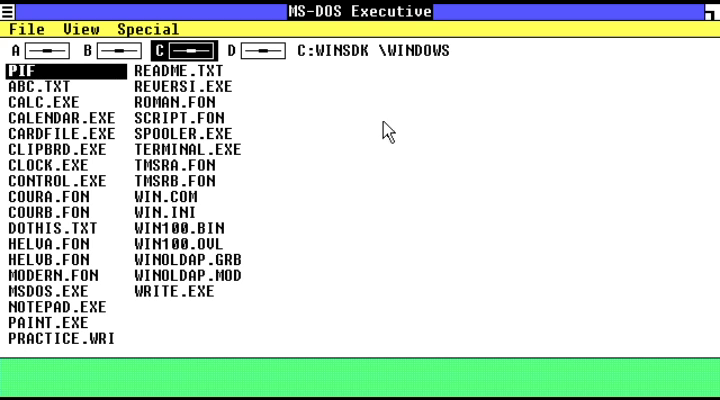

Compared to even the slightly later Windows 2.0, Windows 1.0 is much closer to DOSSHELL than any other version of Windows, and is essentially a graphical bolt-on to DOS although through deep magic, it is capable of cooperative multitasking. This was done entirely with software trickery as Windows pre-dates the 80286, and ran on the original 8086. COMMAND.COM could be run as a text-based application, however, most DOS applications would launch a full-screen session and take control of the UI.

This is likely why Windows 1.0 has issues on later versions of DOS as it’s likely taking control of internal structures within DOS to perform borderline magic on a processor that had no concept of memory protection.

Another oddity is that this version of Windows doesn’t actually have “windows” per say. Instead applications are tiled, with only dialogue boxes appearing as free-floating Windows. Overlapping Windows would appear in 2.0, but it’s clear from the API that they were at least planned for at some point. Most notable, the CreateWindow() function call has arguments for x and y coordinates.

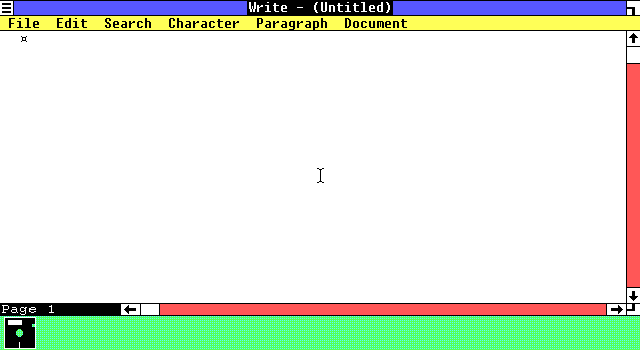

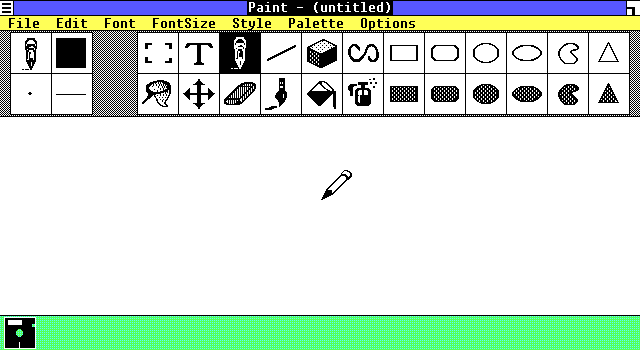

My best guess is Microsoft wished to avoid the wrath of Apple who had gone on a legal warpath of any company that too-closely copied the UI of the then-new Apple Macintosh. Compared to later versions, there are also almost no included applications. The most notable applications that were included are: NOTEPAD, PAINT, WRITE, and CARDFILE.

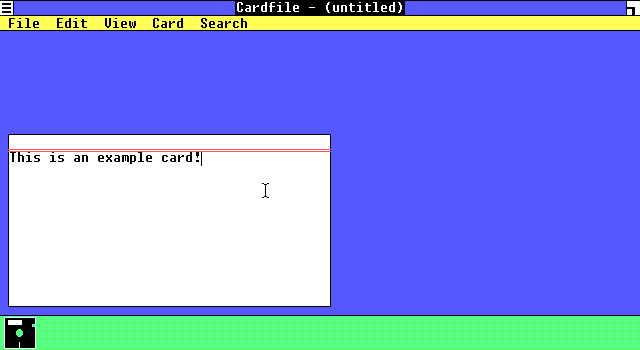

While NOTEPAD is essentially unchanged from its modern version, Write could be best considered a stripped-down version of Word, and would remain a mainstay until Windows 95 where it was replaced with Wordpad. CARDFILE likewise was a digital Rolodex. CARDFILE remained part of the default install until Windows 3.1, and remained on the CD-ROM for 95, 98, and ME before disappearing entirely.

PAINT, on the other hand, is entirely different from the Paintbrush application that would become a mainstay. Specifically, it’s limited to monochrome graphics, and files are saved in MSP format. Part of this is due to limitations of the Windows API of the era: for drawing bitmaps to the screen, Windows provided Display Independent Bitmaps or DIBs. These had no concept of a palette and were limited to the 8 colors that Windows uses as part of the EGA palette. Color support appears to have been a late addition to Windows, and seemingly wasn’t fully realized until Windows 3.0.

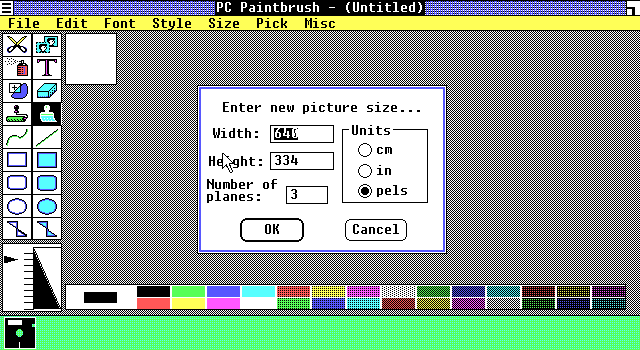

Paintbrush (and the later and confusingly-named Paint) was actually a third party application created by ZSoft which had DOS and Windows 1.0 versions. ZSoft Paintbrush was very similar to what shipped in Windows 3.0 and used a bit of technical trickery to take advantage of the full EGA palette.

With that quick look completed, let’s go back to actually getting to HELLO.C, and that involved getting the SDK installed.

The Windows SDK and Microsoft C 4.0

Getting the Windows SDK setup is something of an experience. Most of Microsoft’s documentation for this era has been lost, but the OS/2 Museum has scanned copies of some of the reference binders, and the second disk in the SDK has both a README file and an installation batch file that managed to have most of the necessary information needed.

Unlike later SDK versions, it was the responsibility of the programmer to provide a compiler. Officially, Microsoft supported the following tools:

- Microsoft Macro Assembler (MASM) 4

- Microsoft C 4.0 (not to be confused with MSC++4, or Visual C++)

- Microsoft Pascal 3.3

Unofficially (and unconfirmed), there were versions of Borland C that could also be used, although this was untested, and appeared to not have been documented beyond some notes on USENET. More interestingly, all the above tools were compilers for DOS, and didn’t have any specific support for Windows. Instead, a replacement linker was shipped in the SDK that could create Windows 1.0 “NE” New Executables, an executable format that would also be used on early OS/2 before being replaced by Portable (PE) and Linear Executables (LX) respectively.

For the purposes of compiling HELLO.C, Microsoft C 4.0 was installed. Like Windows, MSC could be run from floppy disk, albeit it with a lot of disk swapping. No installer is provided, instead, the surviving PDFs have several pages of COPY commands combined with edits to AUTOEXEC.BAT and CONFIG.SYS for hard drive installation. It was also at this point I installed SLED, a full screen editor as DOS 3.3 only shipped with EDLIN. EDIT wouldn’t appear until DOS 5.0

After much disk feeding and some troubleshooting, I managed to compile a quick and dirty Hello World program for DOS. One other interesting quirk of MSC 4.0 was it did not include a standalone assembler; MASM was a separate retail product at the time. With the compiler sorted, it was time for the SDK.

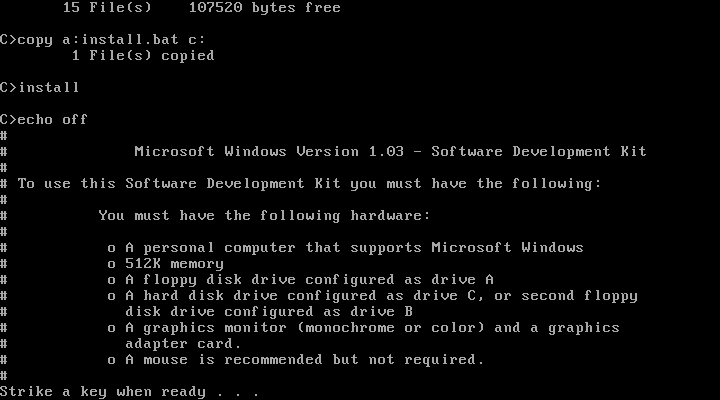

Fortunately, an installation script is provided. Like SELECT, it required listing out a bunch of folders, but otherwise was simple enough to use. For reasons that probably only made sense in 1985, both the script and the README file was on Disk 2, and not Disk 1. This was confirmed not to be a labeling error as the script immediately asks for Disk 1 to be inserted.

The install script copies files from four of the seven disks before returning to a command line. Disk 5 contains the debug build of Windows, which are roughly equivalent to checked builds of modern Windows. Disk 6 and 7 have sample code, including HELLO.C.

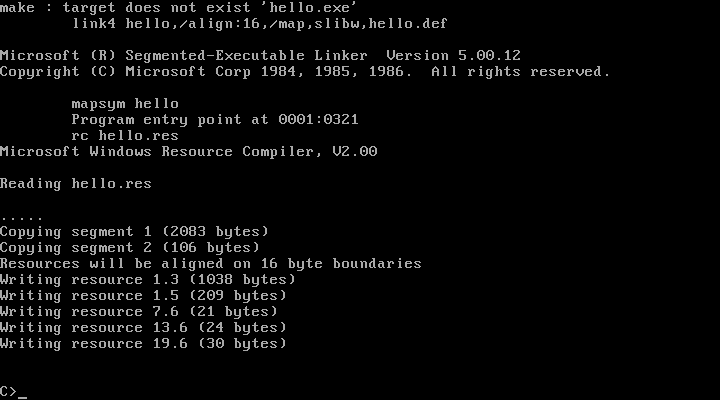

With the final hurdle passed, it wasn’t too hard to get to compiled HELLO.EXE.

Dissecting HELLO.C

I’m going to go through these at a high level, my annotated hello.c goes into much more detail on all these points.

General Notes

Now that we can build it, it’s time to take a look at what actually makes up the nuts and bolts of a 16-bit Windows application. The first major difference, simply due to age is that HELLO.C uses K&R C simply on the basis of pre-dating the ANSI C function. It’s also clear that certain conventions weren’t commonplace yet: for example, windows.h lacks inclusion guards.

NEAR and FAR pointers

long FAR PASCAL HelloWndProc(HWND, unsigned, WORD, LONG);

Oh boy, the bane of anyone coding in real mode, near and far pointers are a “feature” that many would simply like to forget. The difference is seemingly simple, a near pointer is nearly identical to a standard pointer in C, except it refers to memory within a known segment, and a far pointer is a pointer that includes the segment selector. Clear right?

Yeah, I didn’t think so. To actually understand what these are, we need to segue into the 8086’s 20-bit memory map. Internally, the 8086 was a 16-bit processor, and thus could directly address 2^16 bits of memory at a time, or 64 kilobytes in total. Various tricks were done to break the 16-bit memory barrier such as bank switching, or in the case of the 8086, segmentation.

Instead of making all 20-bits directly accessible, memory pointers are divided into a selector which forms the base of a given pointer, and an offset from that base, allowing the full address space to be mapped. In effect, the 8086 gave four independent windows into system memory through the use of the Code Segment (CS), Data Segment (DS), Stack Segment (SS), and the Extra Segment (ES).

Near pointers thus are used in cases where data or a function call is in the same segment and only contain the offset; they’re functionally identical to normal C pointers within a given segment. Far pointers include both segment and offset, and the 8086 had special opcodes for using these. Of note is the far call, which automatically pushed and popped the code segment for jumping between locations in memory. This will be relevant later.

HelloWndProc is a forward declaration for the Hello Window callback, a standard feature of Windows programming. Callback functions always had to be declared FAR as Windows would need to load the correct segment when jumping into application code from the task manager. Hence the far declaration. Windows 1.0 and 2.0, in addition, had other rules we’ll look at below.

WinMain Decleration:

int PASCAL WinMain( hInstance, hPrevInstance, lpszCmdLine, cmdShow ) HANDLE hInstance, hPrevInstance; LPSTR lpszCmdLine; int cmdShow;

PASCAL Calling Convention

Windows API functions are all declared as PASCAL calling convention, also known as STDCALL on modern Windows. Under normal circumstances, the C programming language has a nominal calling convention (known as CDECL) which primarily relates to how the stack is cleaned up after a function call. In CDECL-declared functions, its the responsibility of the calling function to clean the stack. This is necessary for vardiac functions (aka, functions that take a variable number of arguments) to work as the callee won’t know how many were pushed onto the stack.

The downside to CDECL is that it requires additional prologue and epilogue instructions for each and every function call, thereby slowing down execution speed and increasing disk space requirements. Conversely, PASCAL calling convention left cleanup to be performed by the called function and usually only needed a single opcode to clean the stack at function end. It was likely due to execution and disk space concerns that Windows standardized on this convention (and in fact still uses it on 32-bit Windows.

hPrevInstance

if (!hPrevInstance) {

/* Call initialization procedure if this is the first instance */

if (!HelloInit( hInstance ))

return FALSE;

} else {

/* Copy data from previous instance */

GetInstanceData( hPrevInstance, (PSTR)szAppName, 10 );

GetInstanceData( hPrevInstance, (PSTR)szAbout, 10 );

GetInstanceData( hPrevInstance, (PSTR)szMessage, 15 );

GetInstanceData( hPrevInstance, (PSTR)&MessageLength, sizeof(int) );

}

hPrevInstance has been a vestigial organ in modern Windows for decades. It’s set to NULL on program start, and has no purpose in Win32. Of course, that doesn’t mean it was always meaningless. Applications on 16-bit Windows existed in a general soup of shared address space. Furthermore, Windows didn’t immediately reclaim memory that was marked unused. Applications thus could have pieces of themselves remain resident beyond the lifespan of the application.

hPrevInstance was a pointer to these previous instances. If an application still happened to have its resources registered to the Windows Resource Manager, it could reclaim them instead of having to load them fresh from disk. hPrevInstance was set to NULL if no previous instance was loaded, thereby instructing the application to reload everything it needs. Resources are registered with a global key so trying to register the same resource twice would lead to an initialization failure.

I’ve also gotten the impression that resources could be shared across applications although I haven’t explicitly confirmed this.

Local/Global Memory Allocations

NOTE: Mostly cribbled off Raymond Chen’s blog, a great read for why Windows works the way it does.

pHelloClass = (PWNDCLASS)LocalAlloc( LPTR, sizeof(WNDCLASS) ); LocalFree( (HANDLE)pHelloClass );

Another concept that’s essentially gone is that memory allocations were classified as either local to an application or global. Due to the segmented architecture, applications have multiple heaps: a local heap that is initialized with the program and exists in the local data segment, and a global heap which requires a far pointer to make access to and from.

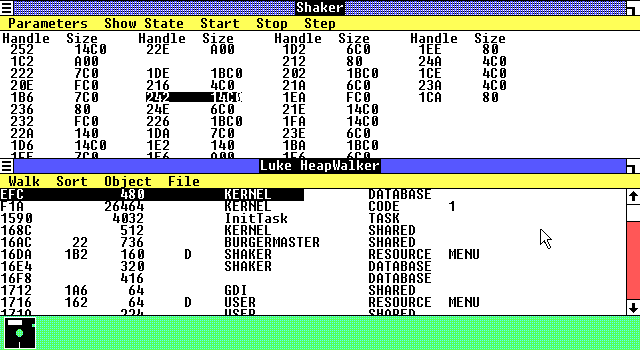

Every executable and DLL got their own local heaps, but global heaps could be shared across process boundaries, and as best I can tell, weren’t automatically deallocated when a process ended. HEAPWALK could be used to see who allocated what and find leaks in the address space. It could also be combined with SHAKER which rearranged blocks of memories in an attempt to shake loose bugs. This is similar to more modern-day tools like valgrind on Linux, or Microsoft’s Application Testing tools.

MakeProcInstance

lpprocAbout = MakeProcInstance( (FARPROC)About, hInstance );

Oh boy, this is a real stinker and an entirely unnecessary one at that. MakeProcInstance didn’t even make it to Windows 3.1 and its entire existence is because Microsoft forgot details of their own operating environment. To explain, we’re going to need to dig a bit deeper into segmented mode programming.

MakeProcInstance’s purpose was to register a function suitable as a callback. Only functions that have been marked with MPI or declared as an EXPORT in the module file can be safely called across process boundaries. The reason for this is that Windows needs to register the Code Segment and Data Segment to a global store to make function calls safely. Remember, each application had its own local heap which lived in its own selector in DS.

In real mode, doing a CALL FAR to jump to a far pointer automatically push and popped the code segment as needed, but the data segment was left unchanged. As such, a mechanism was required to store the additional information needed to find the local heap. So far, this is sounding relatively reasonable.

The problem is that 16-bit Windows has this as an invariant: DS = SS …

If you’re a real mode programmer, that might make it clear where I’m going with this. The Stack Segment selector is used to denote where in memory the stack is living. SS also got pushed to the stack during a function call across process boundaries along with the previous SP. You might begin to see why MakeProcInstance becomes entirely unnecessary.

Instead of needing a global registration system for function calls, an application could just look at the stack base pointer (bp) and retrieve the previous SS from there. Since SS = DS, the previous data segment was in fact saved and no registration is required, just a change to how Windows handles function epilogs and prologs. This was actually found by a third party, and a tool FixDS was released by Michael Geary that rewrote function code to do what I just described. Microsoft eventually incorporated his fix directly into Windows, and MakeProcInstance disappeared as a necessity.

Other Oddities

From Raymond Chen’s blog and other sources, one interesting aspect of 16-bit Windows was it was actually designed with the possibility that applications would have their own address space, and there was talk that Windows would be ported to run on top of XENIX, Microsoft’s UNIX-based operating system. It’s unclear if OS/2’s Presentation Manager shared code with 16-bit Windows although several design aspects and API names were closely linked together.

From the design of 16-bit Windows and playing with it, what’s clear is this was actually future-proofing for Protected Mode on the 80286, sometimes known as segmented protection mode. On 286’s Protected Mode, while the processor was 32-bit, the memory address space was still segmented into 64-kilobyte windows. The primary difference was that the segment selectors became logical instead of physical addresses.

Had the 80286 actually succeeded, 32-bit Windows would have been essentially identical to 16-bit Windows due to how this processor worked. In truth, separate address spaces would have to wait for the 80386 and Windows NT to see the light of day, and this potential ability was never used. The 80386 both removed the 64-kilobyte limit and introduced a flat address space through paging which brought the x86 processor more inline with other architectures.

Backwards Compatibility on Windows 3.1

While Microsoft’s backward compatibility is a thing of legend, in truth, it didn’t actually start existing until Windows 3.1 and later. Since Windows 1.0 and 2.0 applications ran in real mode, they could directly manipulate the hardware and perform operations that would crash under Protected Mode.

Microsoft originally released Windows 286, and 386 to add support for the 80286 and 80386, functionality that would be merged together in Windows 3.0 as Standard Mode, and 386 Enhanced Mode along with legacy “Real Mode” support. Due to running parts of the operating system in Protected Mode, many of the tricks applications could perform would cause a General Protection Fault and simply fail. This wasn’t seen as a problem as early versions of Windows were not popular, and Microsoft actually dropped support for 1.x and 2.x applications in Windows 95.

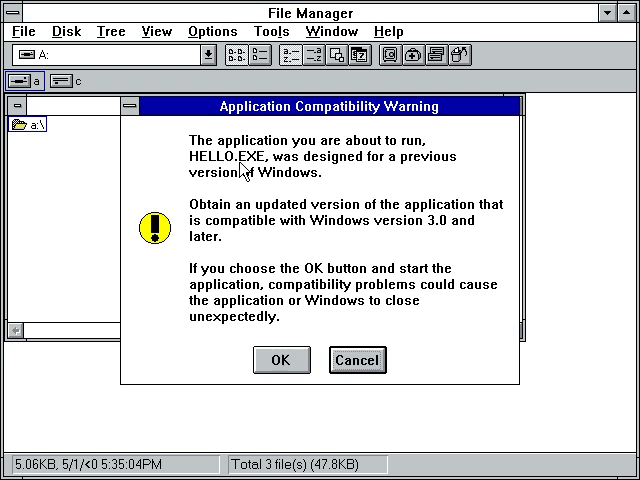

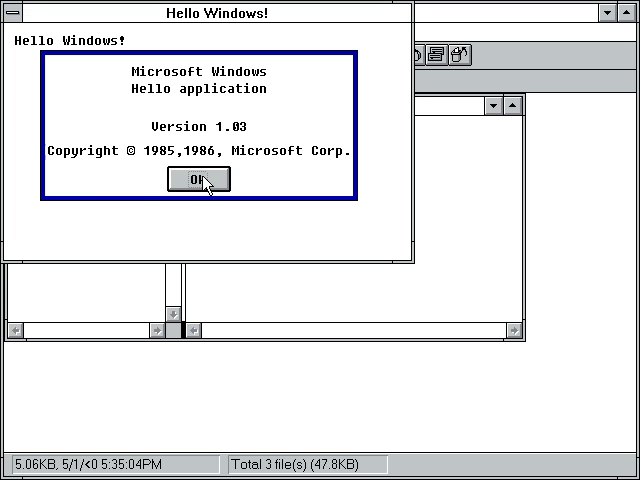

Windows for Workgroups was installed in a fresh virtual machine, and HELLO.EXE, plus two more example applications, CARDFILE and FONTTEST were copied with it. Upon loading, Windows did not disappoint throwing up a compatibility warning right at the get-go.

Accepting the warning showing that all three applications ran fine, albeit it with a broken resolution due to 0,0 being passed into CreateWindow().

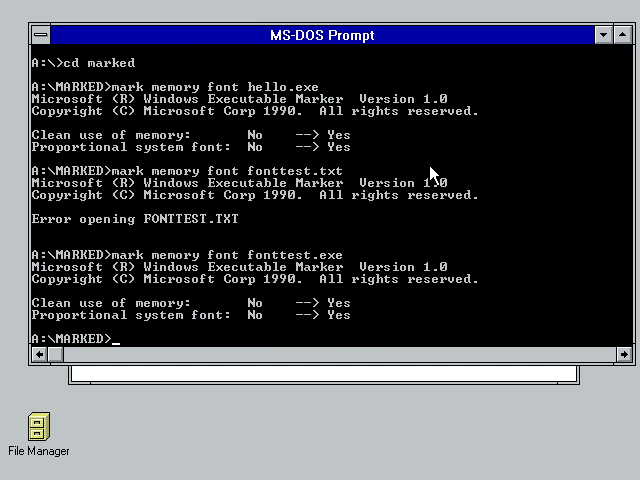

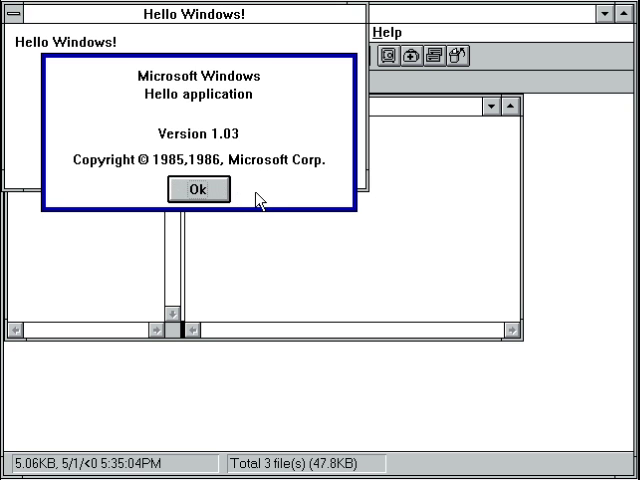

However, there’s a bit more to explore here. The Windows 3.1 SDK included a utility known as MARK. MARK was used, as the name suggests, to mark legacy applications as being OK to run under Protected Mode. It also could enable the use of TrueType fonts, a feature introduced back in Windows 3.0.

The effect is clear, HELLO.EXE now renders in TrueType fonts. The reason TrueType fonts are not immediately enabled can be see in FONTTEST, where the system typeface now overruns several dialog fields.

The question now was, can we go further?

35 Years Later …

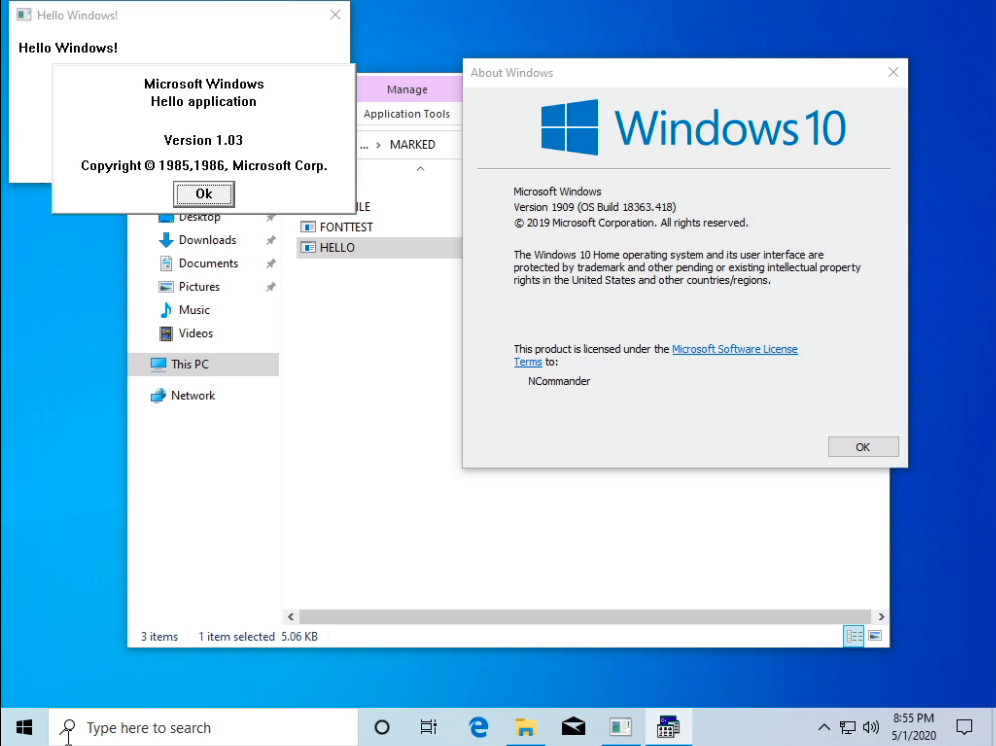

As previously noted, Windows 95 dropped support for 1.x and 2.x binaries. The same however was not true for Windows NT, which modern versions of Windows are based upon. However, running 16-bit applications is complicated by the fact that NTVDM is not available on 64-bit installations. As such, a fresh copy of Windows 10 32-bit was installed.

Some pain was suffered convincing Windows that I didn’t want to use a Microsoft account to sign in. Inserting the same floppy disk as used in the previous test, I double-clicked HELLO and Feature Installer popped up asking to install NTVDM. After letting NTVDM install, a second attempt shows, yes, it is possible to run Windows 1.x applications on Windows 10.

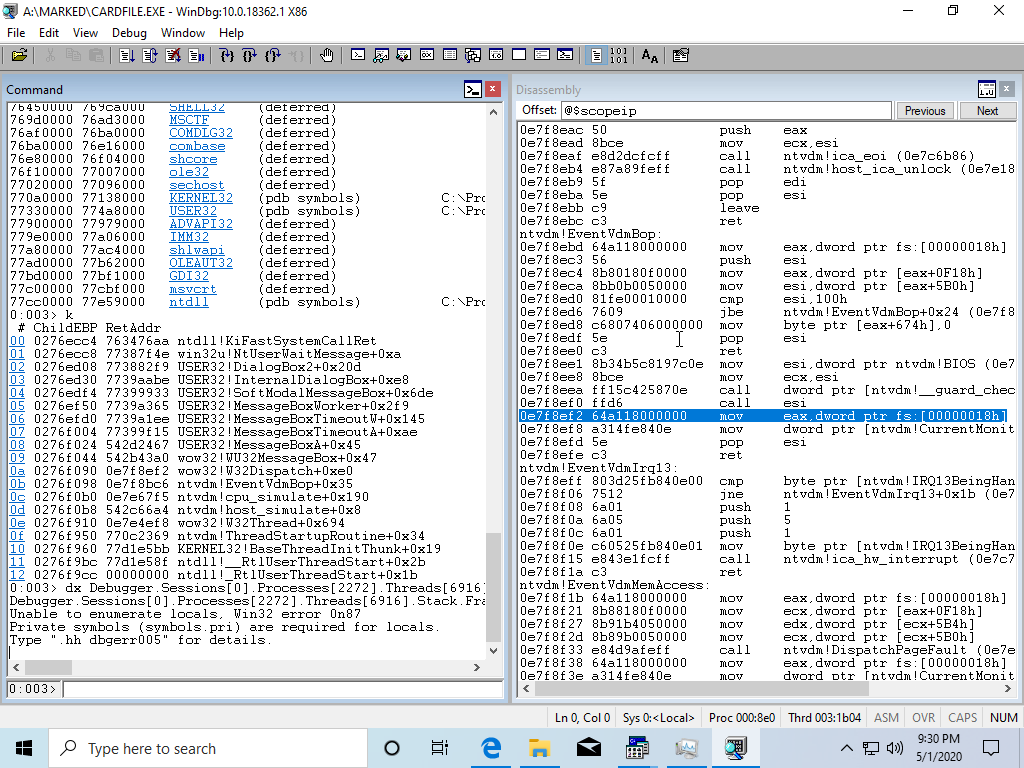

FONTTEST also worked without issue, although the TrueType fonts from Windows 3.1 had disappeared. CARDFILE loaded but immediately died with an initialization error. I did try debugging the issue and found WinDbg at least has partial support for working with these ancient binaries, although the story of why CARDFILE dies will have to wait for another day.

In Closing …

I do hope you enjoyed this look at ancient Windows and HELLO.C. I’m happy to answer questions, and the next topic I’m likely going to cover is a more in-depth look at the differences between Windows 3.1 and Windows for Workgroups combined with demonstrating how networking worked in those versions.

Any feedback on either the article, or the video is welcome to help me improve my content in the future.

Until next time,

73 de NCommander

Windows 9x could load these ancient binaries if the resources are converted. See: http://toastytech.com/guis/misc.html

WineVDM can run early Win16 programs on x64 versions of Windows without modification.

In 16 bit Windows, the final executable is created by the resource compiler, which gets to stamp the OS version. If the resources are converted, is the final executable restamped with a 3.0 version?

As far as I know, Win9x had a hard block on attempting to load Windows 2.x binaries; the warning dialog in 3.x just became a rejection dialog, and IIRC, it rejects applications marked as 3.0 compatible also. For some reason that I don’t know, this check never found its way to NT which is why we see people showing ancient applications running on current versions of Windows.

But as far as resources, something I commented on in this blog and elsewhere in the past is that all I needed to get Word for Windows 1.1 to run on current versions was to upgrade the icons, although it’s true that using a 3.0 resource compiler also upgrades all the dialogs too. Icon handling code for Windows 2.x was removed shortly after NT 3.1, which broke Word 1.1 at the time. After the source release I can see this happening, but it’s a very serious issue because it’s so common for a Windows program to call LoadIcon to associate an icon with its window on initialization. So the 2.x programs that still work are either too trivial to do a very basic thing that any normal application would do, or are so badly coded that they don’t notice that their call to LoadIcon is failing.

With Windows NT, it uses a different method of running 16-bit software. Windows 95/98/ME are basically evolutions of Windows 3.1 and run off the same protected mode kernel that started in Win386.

Windows NT on the other hand uses NTVDM and is running essentially a separate copy of Windows with a different loader. Part of the support may be that PM for NT for OS/2 software was a thing and OS/2 16-bit applications are very close to Windows 1.x/2.x ones. That being said, it is an anomoly, but Windows itself could load those 1.x/2.x resources until Vista.

WineVDM is an add-on software. I’m aware of it, but one could write add-on software to run OS/2 applications under Linux (Twine project). This is what Windows 32-bit does out of the box. I do think the reasoning on removing NTVDM is kinda poor, but I did want to demonstrate this compatibility was like with what you get in the box.

I also don’t count resource conversion because again because it’s conceptually no different than hex editing and replacing components of the original software. Both of these things are legit ways to run old Windows software, but the point here was demonstrating what worked as is.

MakeProcInstance is required in one case, DLLs in real mode. If their data segments are movable they can disappear if they are relocated. In protected mode they’re selectors so they can just set ds as a fixup directly when the DLL is loaded.

I’d have to dig into the SDK documents, but anything declared as EXPORT (aka, old __dllexport) should automatically get registered; a lot of documents I read state that MakeProcInstance isn’t required in that case. You are right that DLLs on 16-bit Windows are a *special* beast though.

Granted, you might still need to MakeProcInstance there if you’re calling a non-exported symbol.

Seems my recollection is wrong as Fixds says that windows does fix the function prolog when the data segment moves which makes sense otherwise every exported function would require makeprocinstance.

If my memory serves, one source of errors trying to run some Windows 1.x/2.x apps in protected mode was that the initial prologue code would try to access the word at ES:2Ch (which in a DOS program would be the environment segment). It never actually did anything with the word having read it, and if that instruction was NOPped out the application would start up without the error.

That might be true with hand written assembly or Pascal applications. I used MSC4.0 for this and didn’t modify any of the source code or resulting binaries aside from the MARK command.

I’d actually expect that behavior though from the few programs that were shipped as Windows runtime like PageMaker which simply included a stripped down Windows 1.0 on the disk. I’d have to check the VM, the headers and the docs, but I’m not certain if Win 1.0 has the concept of CLI switches or the APIs to handle them.

You have the answer in front of you. In WinMain, the parameter “LPSTR lpszCmdLine;” is a Long Pointer to a Strtring terminanted in null that returns the command line.

There are days where it pays to drink coffee before answering the question >.<;

What I was thinking of anything that covers up WinMain, requiring to get the cmdline via GetCommandLine()

Figured people on this post would appreciate this – compiling apps on the much earlier Windows 1 alpha builds – https://www.betaarchive.com/forum/viewtopic.php?f=59&t=41648

Oooh, neat. I’ve been told OpenWatcom can actually produce the correct format binaries, but its headers are just too new to actually get something working, combined with sheer magic in the vanilla Windows C library that just makes it hard.

I do wonder if those early MSC disks will ever show up …